An Early Narrative of Map History

/Rufus Blanchard’s Historical Map of the United States (1876)

Here’s another little blip that I’ve had to cut out of Maps, History, Theory that can sort of stand by itself. I was going to use this as the introductory “hook” for the chapter on traditional map history, but the reworking of the previous chapters means that it no longer works. While I might mention the topic, it’s too minor to get so much coverage in the book. I’ve reworked the material and I’ve also expanded it with some digressions …

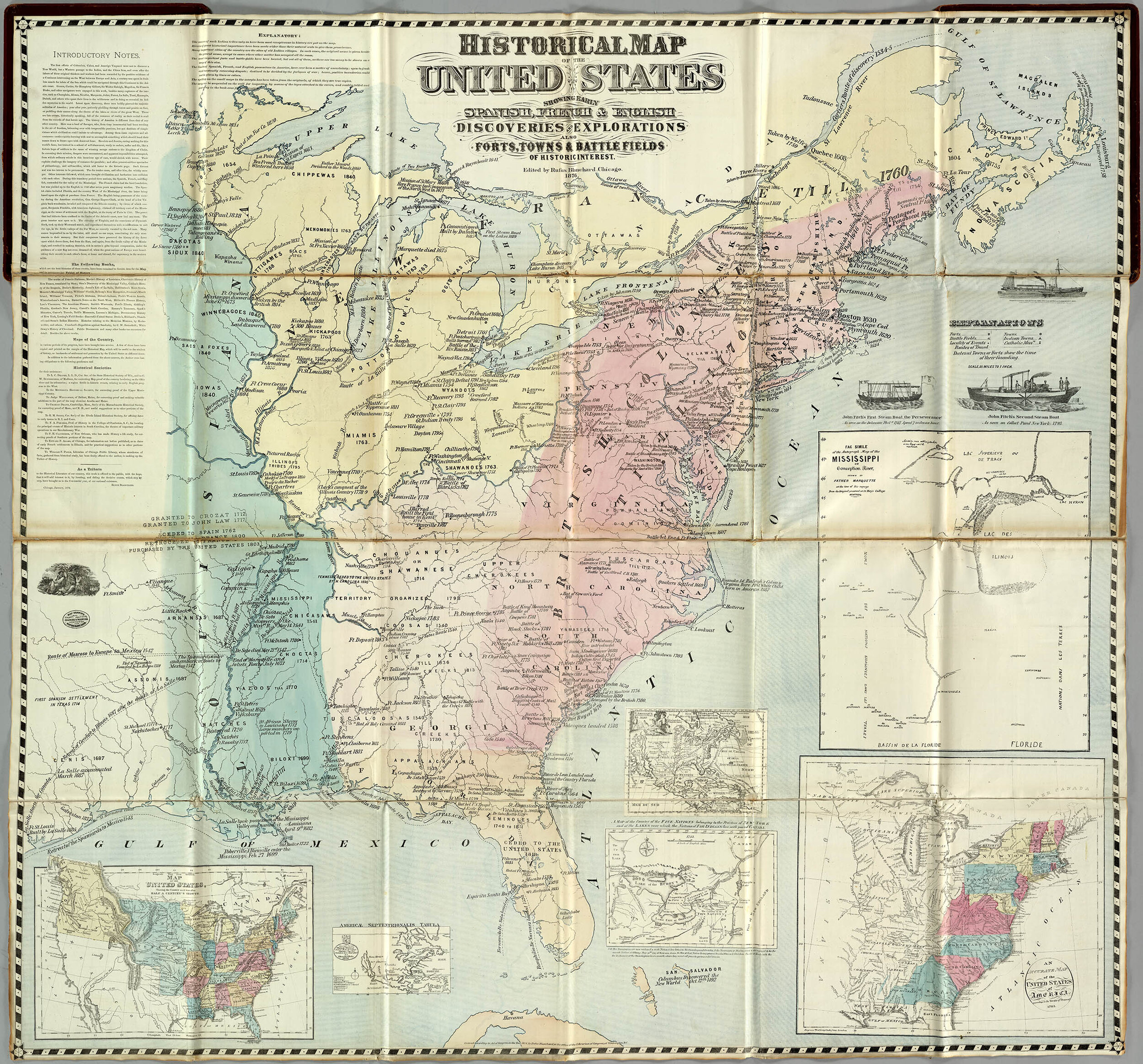

Here is an early work of traditional map history in map form [n1]:

Fig. 1. Rufus Blanchard, Historical Map of the United States, Showing Early Spanish, French & English Discoveries and Explorations, and Forts, Towns & Battle Fields of Historic Interest. Edited by Rufus Blanchard (Chicago, 1876). Issued folded, in boards. Color lithograph, 137 × 145 cm. Courtesy of David Rumsey (3967.001); www.davidrumsey.com. Click on map for high-res image.

It was prepared by Rufus Blanchard—a publisher, photographer, map maker, and historian, born in New Hampshire in 1821, who worked in Chicago from 1854 to 1904 (Selmer 1984)—and published in January 1876 in commemoration of the centennial of the US Declaration of Independence. A large map, measuring 137 × 145 cm (4′6″ × 4′9″), it was mounted on cloth and housed in sturdy covers. It was also backed with a long chronology of key events in US history, which Blanchard called a Tablet of History:

Fig. 2. Rufus Blanchard, Tablet of History Outlining the Discovery and Exploration of America, and the Settlement, Wars and Civil Progress of the United States, from Her Colonial Beginning to 1876, verso of his Historical Map of the United States (Chicago: Rufus Blanchard, 1876). Courtesy of David Rumsey (3967.000); www.davidrumsey.com. Click on “tablet” for high-res image.

The version in David Rumsey’s collection lacks them, but the map was sold with looped cloth “tapes” to permit the whole to be suspended on a wall to display either side. A note added to the map explained that the work could be folded up for easy storage (below). (One of OML’s two copies shows extensive wear along the folds and the cloth loops: it has been nicely imaged.)

There is much to be said about this large wall map in its construction of US history and national identity. The rhetoric of the map and of the Tablet of History makes them an instructive read, and I recommend them to anyone who teaches or studies US history in the post-Civil War period. Blanchard was very much a proponent of the USA as a WASP country—White, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant—and he consistently referred to the mother country as England, never Britain (with all its Celtic elements!). Susan Schulten (2012, 57–59) has discussed the manner in which Blanchard selected and mapped out the events (discoveries and battles), places (towns and forts), and routes of explorers that Blanchard deemed of significance to US history. He began with the discoveries of Columbus and the Cabots and continued to the 1876.

The map uses color to show the imperial divisions of eastern North America as they existed at the time of the Revolution: the province of Quebec, as defined by the British government in 1774, in pale yellow; the thirteen original colonies of the USA, in pink; the western lands annexed from France in 1763, uncolored; and the edge of Louisiana, in green, hinting at the republic’s later westward expansion. Schulten noted the vagueness of Blanchard’s depiction of political divisions, his blurring of the edges of imperial control, and how he widened “rivers of great historical importance…to give them prominence,” as the map’s explanatory notes also stated:

Detail of explanatory notes from Fig. 1

Blanchard described himself in the map’s title as the “editor” of the map, asserting that he had simply assembled facts rather than created a complex narrative. He even gave, within the text covering the far west, a bibliography of the histories and accounts that he had used for the map and the chronology.

Detail of bibliography from Fig. 1

Blanchard thought that this analytical mapping of US history was innovative. A February 1876 account in the Northwestern Chronicle—the kind of puff piece placed by publishers as supposedly disinterested reviews—stated that it was the “first” work “to inaugurate this system of showing history on maps” (quoted by Selmer 1984, esp. 27–28). Blanchard was clearly not the first to do so (see Schulten 2007 on Emma Willard), but he was one of the first in the USA to engage in narrative map history. Blanchard’s narrative was graphic in form, comprising a series of facsimiles of early maps.

Blanchard’s Blurring of Analytical Mapping of the Past and Map History

I should note that it is not clear where the division might be drawn between Blanchard’s analytical mapping and map history. The two lower corners of the map feature two inset maps of the USA in 1783 and after “half a century’s growth.” Blanchard later issued the inset map for 1783 as a separate map, by transferring the original drawing to another lithographic surface for printing. This separate map was advertised in the Chicago Daily Tribune for 14 April 1876. The advertisement gave its price as 25 cents retail and stated that “Everybody wants it”:

Fig. 3. Rufus Blanchard, An Accurate Map of the United States of America According to the Treaty of Peace, 1783 / Map Drawing, Engraving, Printing, Coloring & Mounting Executed in the Best Style, Rufus Blanchard (Chicago: Rufus Blanchard, undated but [1876]). My thanks to Ed Redmond for the image! Courtesy of the Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress (G3701.S4 1860).

The separately map was differentiated by the addition of his business details in the upper-right portion of the map (the same kind of icon found close to the left-hand neat line of the Historical Map.

For this map and that of the USA in 1833, Blanchard seems to have taken maps from those periods and redrew them in the mid-nineteenth-century style of American commercial geographical mapping. I must admit that have not done the work to determine which maps Blanchard used as sources for these two maps, although the map for 1783 is likely derived from one of the maps created directly after the Treaty of Paris (Ristow 1978). In appearance, the two inset maps seemed to be modern analytical maps, which is to say maps made now, that illustrated the USA’s growth over its first half century.

Blanchard’s other four inset maps in the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico, however, were photographic transfers of old maps that were only slightly modified. They looked old, in both their aesthetic and content, and were clearly images of mapping then. Blanchard emphasized the unmediated nature of their reproduction in the explanatory notes (above), where he stated: “The spelling on the small maps in the margin has been taken from the originals, of which they are true copies.” They are indeed close reproductions made at the same size as the originals. The alterations are small, but significant. The result sustained a narrative constructed in line with existing ideas of “American” identity and Manifest Destiny.

Narrating the Discovery and Settlement of the USA

The key change to each facsimile was the addition of a date, in relatively large lettering, to three of the maps. The dates are not necessarily correct, but they indicate how Blanchard expected the maps to be read: as a narrative.

Two of the four facsimiles are of maps that are today well-known within certain cliques of US map historians specializing in the mapping of particular parts of colonial America. The other two are really minor works that are readily identifiable only because of the extensive (obsessive?) work listing maps that show certain geographical features. They are, in Blanchard’s chronological order (and at whatever size the SquareSpace CMS will show them):

1) at the right, the largest of the facsimiles, of a manuscript map of the Mississippi country that has generally been attributed to Jacques Marquette. The facsimile is undated but is supposed to date from Marquette’s voyage in 1673–74. This particular map is well known to historians of the upper Mid-West. Blanchard his image not from the original manuscript, in Montreal (Buisseret and Kupfer 2011; also Kupfer and Buisseret 2019), but from a facsimile thereof by John Gilmary Shea in his Discovery and Exploration of the Mississippi Valley (1852, opp. 268), one of the books in Blanchard’s bibliography.

Detail of fig. 1: Fac Simile of the Autograph Map of the Mississippi or Conception River Drawn by Father Marquette, 43 × 36.5 cm

2) the supposedly “1684” map actually appeared twenty years later, in the first edition of the Latin translation by Edward Wells of the travels of Dionysius Periegetes (1704, opp. 38); it was reprinted in later editions through the eighteenth century (McLaughlin and Mayo 1995, no. 205).

Detail of fig. 1: Edward Wells, Americæ septentrionalis tabula 1684, 8.5 × 15.5 cm

3) the binding instruction reproduced with the “1690” map indicates that it had to have been taken from the first Parisian edition of a minor geographical text by a provincial French scholar (Croix 1693, 4: opp. 273; see Burden 2007, no. 695).

Detail of fig. 1: L’Amerique septentrionale 1690, 14 × 19 cm

4) the 1755 map of the country of the Five Nations—i.e., the Haudenosaunee (called the Iroquois by the French)—was copied from Cadwallader Colden’s map that had been printed in the three London editions of his History of the Five Nations in 1747–55. The source for this photographically transferred facsimile is uncertain: the image matches neither the original impressions nor the known facsimiles thereof [n2].

Detail of fig. 1: A Map of the Country of the Five Nations…1755, 15.5 × 23 cm (neatlines)

By improperly dating Wells’s sketchy and crude map two decades too early, Blanchard placed it earlier than the de la Croix map, which had many more details about the interior, including the Mississippi River. That river and its tributaries, including the Illinois River and its connection to the Great Lakes, which would eventually lead to Chicago’s foundation, were the subject of the large manuscript outlining Marquette’s travels in 1673–74. The suggestion is of the expansion of French knowledge of the continental interior through exploration, hinting at the growth of geographical knowledge and the subsequent rise of colonies. With Colden’s much later map, Blanchard’s then drew attention to the eighteenth-century rise of English power over both the French and the Indians. (Notice the far superior outline of the Great Lakes over Wells’s map.)

The narrative constructed through these maps was extended into the present by the Furthermore, set above the Marquette manuscript are images of three of the first US steam vessels, all designed for river work, with which the continental interiors would be opened up to commercial exploitation in the nineteenth century.

Detail of Fig. 1

At the far left, situated out on the western plains, a further vignette, depicted an English farmer displacing/replacing a despondent native hunter:

Detail of Fig. 1

Combined with the four facsimiles, these vignettes suggest an ongoing movement not only to settle the continent but to advance the “civil progress” of the USA, as the title to the Tablet put it.

Blanchard outlined this interpretation for the reader of the Historical Map. Much of the text on the left-hand side of the map is a summary history of the discovery of North America. Continuing on directly from the bibliography that followed the historical summary, Blanchard then stated:

Besides the above works,

Maps of the Country,

in various periods of its progress, have been brought into service. A few of these have been copied and printed on the margin of the Historical Map, which will be useful to the student of history, as landmarks of settlement and possession by the United States at different times.

Blanchard, working in Chicago, thus recapitulated the first works in the “history of cartography” published in Paris in the 1840s and 1850s. The facsimile collections by Edme François Jomard and by the viscount of Santarém had been designed to allow scholars to compare sequences of early maps so as to develop their own understanding of the growth of geographical knowledge and of Western civilization. But Blanchard turned that larger narrative to the more precise service of the growth of the American nation and the Westward Course of Empire.

Blanchard’s Motivations

I have uncertain where Blanchard got the idea to use early maps in this way. Jomard’s and Santarém’s facsimile collections were large and expensive, few were made, and were unlikely to have reached Chicago (at least, before the Chicago businessman Edward E. Ayer acquired copies for his own library, which became a kernel of the Newberry Library’s great collections). Perhaps Blanchard had been inspired by the German geographer, travel writer, and historian of North American discovery, Johann Georg Kohl, who had passed through Chicago to and from his travels in the upper Mid-West in 1855 (Wolter 1993).

However, the idea of using maps “as landmarks of settlement and possession” to demonstrate the progress of discovery and civilization was well established in the early nineteenth century. A key text, Conrad Malte-Brun’s history of geography in the first volume of his Précis de géographie (1810) would be republished in English editions in the USA (Malte-Brun 1824, 1827). If not these volumes, then the works on discovery that Blanchard mentioned in his bibliography, especially Shea’s (1852) account of Marquette et al. on the Mississippi, might have prompted the use of maps.

I am especially struck by the fact that to construct his narrative of civil progress, Blanchard had to use what today appear to be very minor maps. There are none of the grand manuscript maps that could be found in European libraries, nor even the major printed works, such as Delisle’s maps of the continent that were the basis for Colden’s map. Perhaps the issue was space: Blanchard needed smaller maps to fit in the waters around the USA that would complement and not overwhelm the main map. But it would seem that Blanchard relied on maps that he had in his own library or to which he had access in some other collection. (We cannot look at the books he had in his library because it burned down with his home studio in 1885: Selmer 1984, 28.) Overall, it seems that Blanchard picked up on contemporary intellectual trends in the history of discovery as that field had been turned to support the nationalistic burden of US exceptionalism and manifest destiny.

Notes

n1. “Traditional map history” is the field of study that was often called the “history of cartography” or “historical cartography” between the 1830 and the 1960s. Despite the apparent inclusivity of its name, especially in its use by R. A. Skelton (1972) and his followers, this field of study has actually excluded other scholarly communities that possess different agendas in studying early or historical maps. I therefore call it “traditional map history” to indicate that it constitutes just one kind of map work.

n2. I have identified the following versions of this famous map:

[0] Cadwallader Colden probably first drew this map in 1723, when surveyor general of the province of New York.

[1] New York engraving: Map of the Countrey of the Five Nations (with an ‘e’ in Country) (Stokes 1915, 3:862, 6:259–60; Wheat and Brun 1978, nos. 317–18):

[1.1] William Bradford engraved and printed it as the frontispiece to Colden’s (1724) commentary on recent acts by the colonial legislature. Bradford later advertised it for sale as a separate work at the same time as the printing of Colden’s History of the Five Nations (Colden 1727, 2017; see Dixon 2016, esp. 74).

a) Facsimile (lithograph): in Iconography of Manhattan Island (Stokes 1915, 3: A pl. 2b)

b) Facsimile (lithograph): in Acts of the Privy Council of England, Colonial Series, “Unbound Papers,” vol. 6, 1676–1783, ed. James Munro (London: HMSO, 1912), §336, which summarizes the matters surrounding the 1724 commentary and the rational for the map (bound at end).

c) I must mention, for the sake of completeness, although I refuse to reproduce it here, that the 1724|7 map was used in about 1952 as an advertising piece for Iroquois Indian Head Beer and Ale in Buffalo (with a completely incorrect attribution to “London 1728”)

[1.2] The plate was modified extensively for reprinting in 1737, again as a separate issue.

The NYPL online catalog suggests that there is a facsimile of this map, published by William Loring Andrews in New York in 1868; according to the catalog for the famous Brinley sale, however, that Andrews provided an ornamental title page for a binding for two impressions, one each of 1.2 and 2.1 (Anonymous 1878, 2:95, no. 3446).

[2] London engraving: Map of the Country of the Five Nations

[2.1] A new engraving, very precise in execution, slightly reduced in size, and with the title and explanation moved above and below the neat line, was made by an unknown engraver for a London edition of Colden’s History of the Five Nations and his 1724 commentary (Colden 1747). This work was reissued twice, with the map unchanged, in 1750 and 1755 (Wroth 1934, 178–83). Note that the text below the neat line is in three lines. A recent reproduction is Schulten (2018, 78–79).

a) Facsimile (lithograph), lacking original title (replaced with “Grand Canal Celebration”) and text below, in William Leete Stone, Memoir, Prepared at the Request of a Committee of the Common Council of the City of New York, and Presented to the Mayor of the City, at the Celebration of the Completion of the New York Canals (New York: Corporation of New York, 1825); digitized (NYPL print division). The impression in the NYPL maps division, also digitized, bears a manuscript annotation that gives the catalog title: “Copy of a Map attached to Govr. Colden’s History of the Five Indian Nations, Printed in London A.D. MDCCXLVII.”

b) Facsimile (copper engraved), in Report by a Committee of the Corporation, Commonly Called the New England Company, of Their Proceedings, for the Civilization and Conversion of Indians, Blacks, and Pagans, in the British Colonies in America and the West Indies (London, 1829), opp. 44, see also 5n; my thanks to John Dixon for this reference. Three lines of text below; slightly different spacing than in original.

c) Facsimile (redrawn): in the Sessional Papers of the Legislature of the Province of Ontario 1 (1898): 49. Just two lines of text below.

d) Facsimile: in John Fiske, The Dutch and Quaker Colonies in America (London: Macmillan, 1899) and later editions.

e) Facsimile (copper engraved): unidentified; known from its further (lithographic) reproduction in Blanchard’s Historical Map (1876). Blanchard’s image is definitely from a copy that had redrawn the original. The differences with the original are plain. The toponym “carrying place” is missing in southern Michigan. More obviously, the three lines of text below the map start with different lines: the lines on the original London impressions start “N.B. The Tuscaroras…” / “received to be…” / “The chief Trade…” whereas those on this unidentified facsimile have less space between “NB” and the aligned text which start, “N.B. The Tuscaroras…” / “seventh Nation…” / “far Indians….”

References

Anonymous. 1878. Catalogue of the American Library of the Late Mr. George Brinley, of Hartford, Conn. 3 vols. Hartford, Conn.: Press of the Case Lockwood & Brainard Company.

Buisseret, David, and Carl Kupfer. 2011. “Validating the 1673 ‘Marquette Map.’” Journal of Illinois History 14, no. 4: 261–76.

Burden, Philip D. 2007. The Mapping of North America II: A List of Printed Maps, 1671–1700. Rickmansworth, Herts.: Raleigh Publications.

Colden, Cadwallader, ed. 1724. Papers Relating to An Act of the Assembly of the Province of New-York, For Encouragement of the Indian Trade, &c. and for Prohibiting the Selling of Indian Goods to the French, viz. of Canada. I. A Petition of the Merchants of London to His Majesty, against the said Act. II. His Majesty’s Order in Council, Referring the said Petition to the Lords Commissioners for Trade & Plantation. III. Extract of the Minutes of the said Lords, concerning some Allegations of the Merchants before Them. IV. The Report of the said Lords to His Majesty on the Merchants Petition, and other Allegations. V. The Report of the Committee of Council of the Province of New-York, in Answer to the said Petition. VI. A Memorial concerning the Furr-Trade of New-York, by C. Colden, Esq; With a Map. Published by Authority. New York: William Bradford.

———. 1727. The History of the Five Indian Nations Depending on the Province of New-York in America. New York: William Bradford.

———. 1747. The History of the Five Indian Nations of Canada, Which are dependent On the Province of New-York in America, and Are the Barrier between the English and French in that Part of the World. With Accounts of their Religion, Manners, Customs, Laws, and Forms of Government; their several Battles and Treaties with the European Nations; particular Relations of their several Wars with the other Indians; and a true Account of the present State of our Trade with them. In which are shewn The great Advantage of their Trade and Alliance to the British Nation, and the Intrigues and Attempts of the French to engage them from us; a Subject nearly concerning all our American Plantations, and highly meriting the Consideration of the British Nation at this Juncture. By the Honourable Cadwallader Colden, Esq; One of his Majesty’s Counsel, and Surveyor-General of New-York. To which are added, Accounts of the several other Nations of Indians in North-America, their Numbers, Strength, &c. and the Treaties which have been lately made with them. A Work highly entertaining to all, and particularly useful to the Persons who have any Trade or Concern in that Part of the World. London: T. Osborne. Reprinted as American Culture Series I, reel 12.

———. 2017. The History of the Five Indian Nations Depending on the Province of New-York in America: A Critical Edition. Edited by John M. Dixon and Karim M. Tiro. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Croix, Antoine Phérotée de la. 1693. La geographie universelle, ou nouvelle methode pour apprendre facilement cette science. Contenant le traité de la sphere, la description du globe terrestre & celeste, les parties du monde, divisées en leurs etats, empires, royaumes, republiques, provinces, &c. Paris: Mabre Cramoisy.

Dionysius Periegetes. 1704. Tēs palai kai tēs nyn Oikoumenēs Periēgēsis, sive Dionysii geographia emendata & locupletata. Translated and edited by Edward Wells. Oxford: Sheldonian Theatre.

Dixon, John M. 2016. The Enlightenment of Cadwallader Colden: Empire, Science, and Intellectual Culture in British New York. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Kupfer, Carl, and David Buisseret. 2019. “Seventeenth-Century Jesuit Explorers’ Maps of the Great Lakes and Their Influence on Subsequent Cartography of the Region.” Journal of Jesuit Studies 6, no. 1: 57–70.

Malte-Brun, Conrad. 1810–29. Précis de la géographie universelle, ou description de toutes les parties du monde, sur un plan nouveau d’après les grandes divisions naturelles du globe; précédée de l’histoire de la géographie chez les peuples anciens et modernes, et d’une théorie générale de la géographie mathématique, physique et politique; et accompagnée de cartes, de tableaux analytiques, synoptiques et élémentaires, et d’une table alphabetique des noms de lieux. 8 vols. Paris: Fr. Buisson and Aimé-André.

———. 1824–29. Universal Geography, or a Description of All Parts of the World, on a New Plan, According to the Great Natural Divisions of the Globe; Accompanied with Analytical, Synoptical, and Elementary Tables. 7 vols. Boston: Wells and Lilly.

———. 1827–32. Universal Geography: or a Description of All the Parts of the World on a New Plan, According to the Great Natural Divisions of the Globe; Accompanied with Analytical, Synoptical, and Elementary Tables. 6 vols. Philadelphia: A. Finley; J. Laval and S. F. Bradford.

McLaughlin, Glen, and Nancy H. Mayo. 1995. The Mapping of California as an Island: An Illustrated Checklist. California Map Society, Occasional Paper 5. [Saratoga, Calif.]: California Map Society.

Ristow, Walter W. 1978. “The First Maps of the United States of America.” In La Cartographie au XVIIIe siècle et l’œuvre du comte de Ferraris (1726–1814): Colloque internationale, actes / De Cartografie in de 18e Eeuw en het Werk van Graaf de Ferraris (1726–1814): International Colloquium, Handelingen, 179–90. Collection Histoire Pro Civitate / Historische Uitgraven Pro Civitate, 8s 54. Brussels: Credit Communal de Belgique / Gemeentekrediet van Belgie.

Schulten, Susan. 2007. “Emma Willard and the Graphic Foundations of American History.” Journal of Historical Geography 33, no. 3: 542–64.

———. 2012. Mapping the Nation: History and Cartography in Nineteenth-Century America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 2018. A History of America in 100 Maps. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Selmer, Marsha L. 1984. “Rufus Blanchard: Early Chicago Map Publisher.” In Chicago Mapmakers: Essays on the Rise of the City’s Map Trade, edited by Michael P. Conzen, 23–31. Chicago: Chicago Historical Society for the Chicago Map Society.

Shea, John Gilmary. 1852. Discovery and Exploration of the Mississippi Valley: With the Original Narratives of Marquette, Allouez, Membré, Hennepin, and Anastase Douay. Clinton Hall, N.Y.: Redfield.

Skelton, R. A. 1972. Maps: A Historical Survey of Their Study and Collecting. Edited by David Woodward. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stokes, I. N. Phelps. 1915–28. The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498–1909, Compiled from Original Sources and Illustrated by Photo-Intaglio Reproductions of Important Maps, Plans, Views, and Documents in Public and Private Collections. 6 vols. New York: Robert H. Dodd.

Wheat, James Clements, and Christian F. Brun. 1978. Maps and Charts Published in America before 1800: A Bibliography. Holland Press Cartographica, 3. Rev. ed. London: Holland Press.

Wolter, John A. 1993. “Johann Georg Kohl in America.” In Progress of Discovery/Auf den Spuren der Entdecker: Johann Georg Kohl, edited by Hans-Albrecht Koch, Margrit B. Knewson, and John A. Wolter, 133–58. Graz: Akademisch Druck.

Wroth, Lawrence C. 1934. An American Bookshelf, 1755. Publications of the Rosenbach Fellowship in Bibliography, 3. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.