What Is a “Planisphere”?

/Disambiguating a commonly used term that is potentially culturally biased

The Medea project recently inaugurated a weekly blog, “Chart of the Week,” with a post by Joaquim Gaspar on the “Cantino planisphere (1502).” (The image in the blog roll is a detail of that map.) The announcement prompted me to post a series of tweets (@mhedney) about how map historians have used “planisphere” to refer to different kinds of maps. This variety of usages is evident not only in the Anglophone literature but also in French (planisphère), Dutch (planisfeer), German (planisphäre), and so on. (German also has featured planiglobii, which Keuning (1955, 5) translated as “planiglobe.”) I thought I should expand on the tweet, giving sources, references, and further commentary. A closer look into the term’s usage reveals that it has in part been strongly politically and culturally inflected; “planisphere” should be used in a careful and precise manner.

The history of the usage of “planisphere” follows a pattern I’ve found to be rather common in the field: a word is used a precise way by a certain community; later, people outside that community see the word, parse it literally, and then use the word accordingly. The result is a mix of usages, frequently overlapping, none precise, all complicating historical understudy.

The literal, intuitive meaning of “planisphere” is a flattened sphere, a sphere converted in some way to a plane. It was originally used to refer specifically to a map of the celestial sphere, although in the early modern era its usage was expanded; in the modern era, it has been interpreted more generically by historians. This process is evident in the Oxford English Dictionary (art. “Planisphere” n) which presents a quite general meaning:

A map, chart, or scale formed by the projection of a sphere, or part of one, on a plane; a representation of a hemisphere of the earth, the sky, or the solar system, on a flat surface, usually as a circle.

However, in this instance, the OED does give a further note about specific usage in celestial mapping:

spec. (a) a polar projection of half (or more) of the celestial sphere on to a plane surface, so that the equator and circles parallel to it appear as circles on the plane, esp. as used in a common form of astrolabe; (b) a flat device consisting of a polar projection of the whole of that part of the celestial sphere visible from a particular latitude, viewed through a movable cover with an elliptical opening that can be adjusted to show the part of the heavens visible at a given time of night and season of the year.

The OED’s definitions allude to technical elements (in the references to the recreation of the celestial circles as circles on the plane, and the depiction of hemispheres), but these need to be foregrounded in order to develop a history of the term and of its usage.

Origins: Celestial Mapping

The original, technically precise meaning of “planisphere” stems from the title of a twelfth-century translation into Latin of one of the Arabic manuscripts that have preserved Claudius Ptolemy’s Ἄπλωσις ὲπιφανείας σφαίρας, or Simplification of the Sphere. In 1143, Hermann of Carinthia gave the work the Latin title of Planisphaerium. This title was later perpetuated in the Renaissance, in printed editions of Hermann’s text (Edson and Savage-Smith 2000; Sidoli and Berggren 2007, 37–38).

Stated simply, what Ptolemy described was the stereographic projection, one of the four azimuthal projections used in Antiquity and the Classical era to represent the celestial sphere on a plane. None of the three—the other three being the gnomonic, orthographic, and equidistant projections—were originally used for mapping the terrestrial sphere of the earth. The particular benefit of the stereographic projection was that it was, in modern terms, conformal. That is, shapes are preserved in the transformation from sphere to plane, so that a circle in the heavens (both great circles such as the ecliptic, celestial equators, and the colures and small circles, such as arctic circle) are still circles in the plane (see Lorch 1995). Also, the shapes of the constellations were not distorted. The stereographic projection was used in the construction of the main plates (mater and climates) of astrolabes; the rete of the astrolabe (the mesh of lines and pointers) indicated the locations of particular stars. It was perhaps also used in other formats to map the stars.

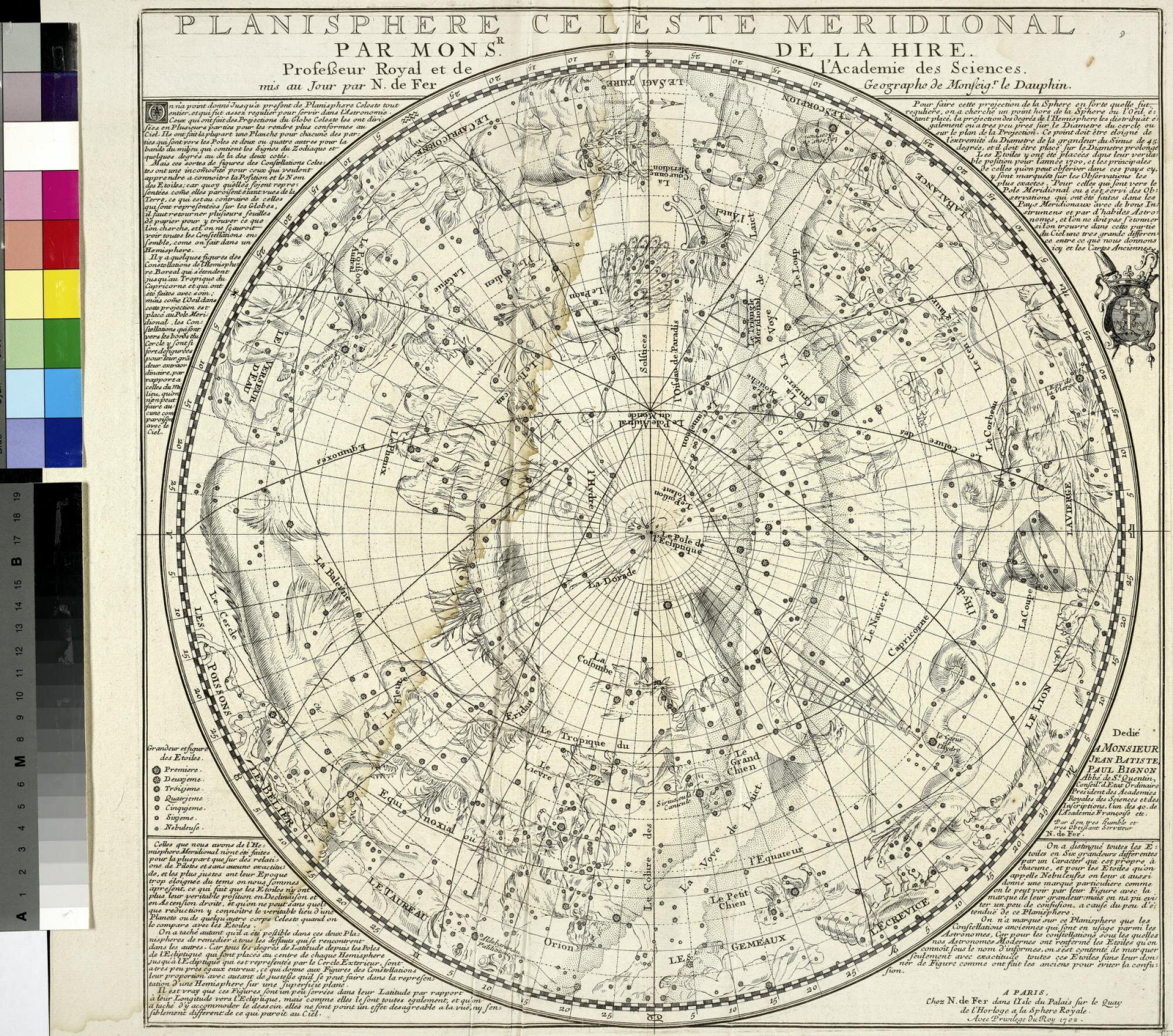

Usage 1: Star Map on the Stereographic Projection

That is, coming out of the medieval period and into the Renaissance, in the Latin West, a planisphere was specifically a star map on the stereographic projection centered on a celestial pole (either equatorial or ecliptic) and generally embracing both the northern celestial hemisphere and those parts of the southern celestial hemisphere that were revealed by the tilt of the earth’s axis. Some early modern star maps covered precisely a hemisphere. Also, a few hemispheres were constructed on the azimuthal equidistant projection, and as such should not be called planispheres (Friedman Herlihy 2007, 105n26). Not that early modern scholars were themselves consistent in their usage.

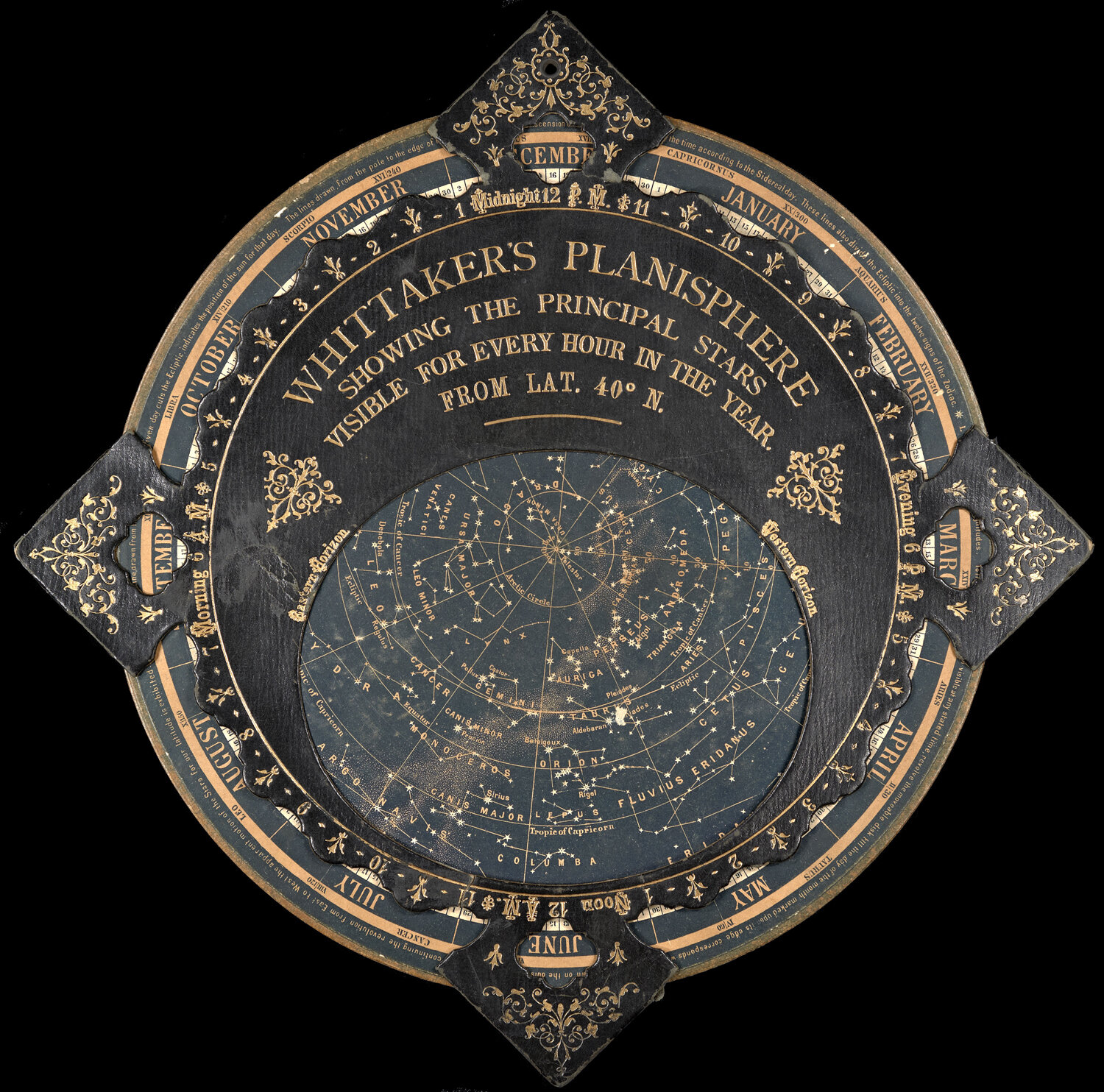

This planisphere depicts one half of the southern celestial sphere, centered on the pole of the ecliptic; the darker solid lines converge at the pole of the equator. Here’s another one, made in a physical casing reminiscent of the astrolabe (but not actually replicating the astronomical instrument; see also Kidwell 2009):

Usage 2: Double Hemisphere World Maps on the Stereographic Projection

At the end of the sixteenth century, Rumold Mercator introduced a new form of world map. Previous geographers had mapped the world in hemispheres, using various projections to shape the hemispheres. Mercator now used the stereographic projection to construct those hemispheres:

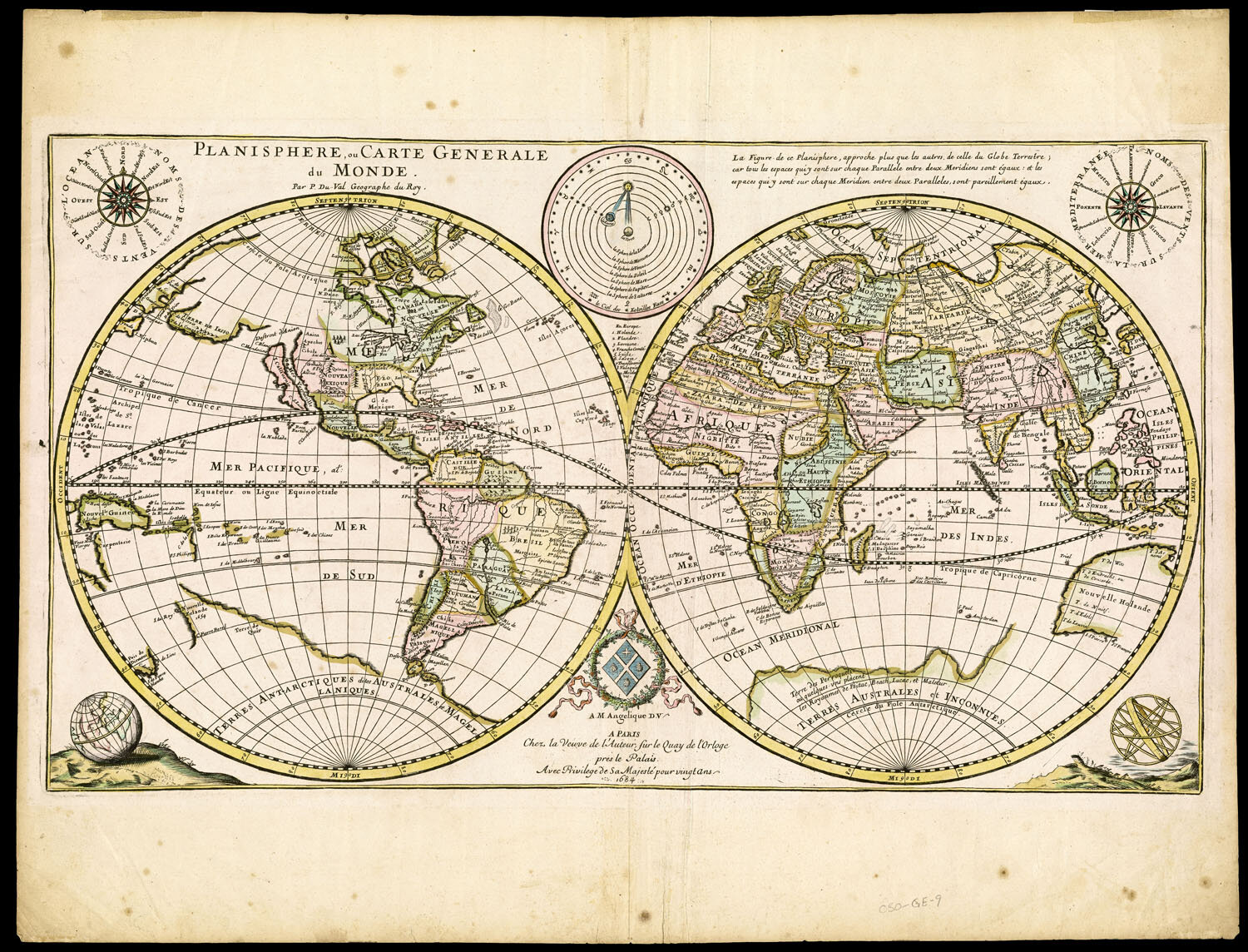

As this style of world map rapidly became dominant among Western map makers, Usage 1 was extended into Usage 2: world map in circular hemispheres on a stereographic projection:

But such maps did not have to be called a planisphere. Generic terms for world maps continued to be used in the titles of such maps, such as mappemonde or universal map.

When map makers began to make maps of the entire night sky in a similar manner, as pairs of hemispheres, they entitled them “planispheres” in the plural, one planisphere per hemisphere (see examples in Warner 1979). This implementation was an appropriate extension of Usage 1. But one work I encountered in my rapid search for this post reveals a possible moment where Usage 2 overwrote proprietary in celestial mapping; in the title to the following, “planisphere” is resolutely singular, suggesting the influence of Usage 2.

Usage 3: Certain World Maps on the Azimuthal Equidistant Projection

The emergence of Usage 3 can be precisely dated. Several early modern map makers produced hemispherical or world maps on the azimuthal equidistant projection. In the 1580s, Urbano Monte made a series of manuscripts, including one in sixty sheets, that would be printed in reduced formats, in which the severe distortion at the extremities of the map were ameliorated by a series of interruptions to make lobes (Anon. 2017; Van Duzer 2020). In 1648, Louis de Mayne Turquet presented this projection as a new invention for which he claimed credit:

This map seems to have influenced Jean Domenique Cassini (I), who in the 1680s famously constructed such a map on the floor of one of the towers in his newly built Paris Observatory. Cassini used this map to plot those locations whose latitudes and longitudes had been carefully determined through astronomical observations; more particularly, those locations whose longitudes had been determined by means of the technique that Cassini I had perfected, of observing the eclipses of the moons of Jupiter as they pass behind the body of the planet. His son, Jacques Cassini (II), had a reduced version of this map engraved and printed in 1696:

Here is Usage 3: the literal meaning of the flattened earth, the circularity, and the astronomical connection seem to have worked together to permit this map to be called a planisphere. Derivative maps of Cassini II’s map were generally also entitled “planispheres.” (See the cover of part 1 of Volume Four of The History of Cartography, at the top of the column at right.)

Usage 4: Any World Map

This is where life gets confusing, much more than I indicated in the original tweet roll. I’ve been looking through my stash of early writings in the history of discoveries and map history, and have realized that commentators, rather than practitioners, began in the later eighteenth century to refer to almost any flat map of the world as a planisphere, in distinction to a globe. (This puts a new slant on the occasional usage of planiglobii or even “planiglob” in English.) That is, they took the word at its etymological, literal, face value.

In 1783, for example, Vincenzio Antonio Formaleoni referred to the circular world map by Andrea Bianco (1436) as a planisferio (see one of my earlier posts), and Placido Zurla (1806, 92) similarly referred to Fra Mauro’s ca. 1450 world map. Such practice followed suit until well into the early nineteenth century.

Usage could become quite confusing. For example, the geographer Marie Armand Pascal d’Avezac inverted eighteenth-century practice:

The work thus produced receives the name mappemonde when structured as two terrestrial hemispheres projected side by side on the plane of one of the great circles of the globe; it is called a planisphere when the entire Earth surface is represented on a flat or reduced projection.

L’oeuvre ainsi produite reçoit le nom de mappemonde, lorsqu’elle offre les deux hémisphères terrestres projetés côte à côte sur le plan de l’un des grands cercles du globe; on l’appelle planisphère lorsque toute la surface Terrestre y est representée sur une projection plate ou reduite. (Avezac 1835, 11)

In other words, d’Avezac made the generic term for “world map” and applied to specifically to world maps of the sort sometimes previously known as planispheres, even as he suggested that planisphere was the generic term for any uninterrupted world map. In the following entry, the Baron Walckenaer (1835, 15, 17) used planisphere to refer to both medieval mappaemundi and to Jacques Cassini’s planisphere, in the latter case again referencing ideas of uninterruptedness, unity, and circularity.

But do not think that a sense of circularity is a crucial element to Usage 4. Edme François Jomard (1844, 449–51) used planisphere to refer to large mappaemundi (Bianco 1436, Hereford, Fra Mauro) and also to Mercator’s great rectangular wall map of 1569 (the one on that projection). This usage was then repeated by d’Avezac (1867) in his summary of Jomard’s great facsimile project, Les monuments de la géographie (1854–62).

Conversely, others were more precise. In writing about the first maps to show Tasmania, R. H. Major (1859, xcv) distinguished between “the mappemonde of Louis Mayerne Turquet, published in Paris in 1648” (see above) and (in the only use of “planisphere” in the entire book) a world map in two hemispheres, the “planisphere, inlaid in the floor of the Groote Zaal, in the Stad-huys at Amsterdam, a building commenced in 1648”:

Other scholars mixed “mappemonde” or “mappamundi” with “planisphere,” using the latter to refer to items from the tenth century, to fourteenth-century marine charts. And so on.

Usages 5 and 6: Post-Medieval World Maps

Usage by commentators settled down somewhat towards the end of the nineteenth century. The prospect of the quadricentennials of Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and Cabotian quadricentennials prompted a significant upsurge in the study of early maps in the 1880s and 1890s that whole heartedly embraced the myth created early in the nineteenth century that medieval scholars believed in a Church-mandated flat earth (Letronne 1834) and the idea that medieval mappaemundi were literal depictions of a flat earth. And as that concept was consolidated, then commentators sought to differentiate the world maps of the Renaissance from those of the benighted middle ages. In this context, usage of “planisphere” shifted to refer to any world map that was not a medieval world map.

So, Usage 5: a planisphere is any world map based on a mathematical projection, as in the OED definition with which I began this post.

And Usage 6: alternatively, a planisphere a map of the world that was drawn in an early marine style (i.e., without the projected graticule of meridians and parallels) and that demonstrated the empirical observation and measurement of the world. Such planispheres might have lacked a proper mathematical structure, but they were manifestly in a different class to the mappaemundi with their crude outlines, imaginary and mythical features, and all-round inadequacies. They proclaimed the rational foundations of the Great Discoveries that contributed to Western rationality. Only at the end of the nineteenth century, with the quadricentennials, do we start to find references to the planispheres of de la Cosa, Cantino, Verrazano, etc. (e.g., Winsor, 1883, 167; Collingridge 1895, 89; Harrisse 1898, 48):

“Cantino planisphere” (1502); Biblioteca Estense, Modena. Image from Wikipedia.

Summary:

a) Avoid Usages 5 and 6

b) Use Only Usage 1 to Refer to a Genre or Style of Map

c) Use Usages 2 and 3 when Recording a Map’s Title

d) Usage 4 Is too imprecise to be Used

Both Usages 5 and 6 are problematic because of the manner in which they construct a dichotomy between medieval and modern mapping that we now know to be false. Both usages are part of the utterly Eurocentric argument that the roots of modern Western culture lie in the Renaissance achievement and the birth of Western rationality, which is to say the same argument that has been used to justify Western imperialism and colonialism with all of their inherent violence physical and enforced distortions of non-Western cultures and societies. Is someone who uses “planisphere” a Eurocentric racist just for using the term in Usages 5 or 6? No, of course not. But I strongly recommend the use of other terminology. In English, we might point to:

• “world map” works quite well, although this can be annoying vague (and “world” is thoroughly malleable!)

• or, for Usage 6, “world map in a marine style.”

I’m ending this post on a strong note because only now, in digging into the literature, have I realized the complexity of Usage 4 and the circumstances in which Usages 5 and 6 developed. At the very least, these usages of “planisphere” are intellectually naive, at worst they embody a distressing Eurocentrism. I need to do much more work on the pattern of usage of this word, and if anyone has counter data, please let me know.

Usage 1 is the only permissible manner in which to refer to a generic group of maps as “planispheres.” Usages 2 and 3 are inconsistent in the early modern record and should appear only in transcriptions of titles.

References

Anonymous. 2017. A Mind at Work: Urbano Monte’s 60-Sheet Manuscript World Map. Stanford, Calif.: David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford University, and Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps.

Avezac, Marie Armand Pascal d’. 1835. “Cartes géographiques.” In Encyclopédie des gens du monde, répertoire universel des sciences, des lettres et des arts: avec des notices sur les principales familles historiques et sur les personnages célèbres, morts et vivans, par une société de savans, de littérateurs et d’artistes, français et étrangers, 5.1: 9–11. 22 vols. Paris: Treuttel et Würtz.

———. 1867. “Inventaire et classement raisonné des Monuments de la Géographie publiés par M. Jomard de 1842 à 1862.” Comptes-rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 11: 230–36.

Collingridge, George. 1895. The Discovery of Australia: A Critical, Documentary and Historic Investigation Concerning the Priority of Discovery in Australasia by Europeans before the Arrival of Lt. James Cook, in the ‘Endeavour,’ in the Year 1770. Sydney: Hayes Brothers.

Edson, Evelyn, and Emily Savage-Smith. 2000. “An Astrologer’s Map: A Relic of Late Antiquity.” Imago Mundi 52: 7–29.

Friedman Herlihy, Anna. 2007. “Renaissance Star Charts.” In Cartography in the European Renaissance, edited by David Woodward, 99–122. Vol. 3 of The History of Cartography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Harrisse, Henry. 1898. “The Outcome of the Cabot Quater-Centenary.” American Historical Review 4, no. 1: 38–61.

Jomard, Edme François. 1844. “Cartes géographiques.” In Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle: Répertoire universel des sciences, des lettres et des arts, edited by Ange de Saint-Priest, 6: 557–76. Paris: Bureaux.

Keuning, Johannes. 1955. “The History of Geographical Map Projections until 1600.” Imago Mundi 12: 1–24.

Kidwell, Peggy Aldrich. 2009. “The Astrolabe for Latitude 41°N of Simeon de Witt: An Early American Celestial Planisphere.” Imago Mundi 61: 91–96.

Letronne, Antoine Jean. 1834. “Des opinions cosmographiques des pères de l’église.” Revue des deux mondes 1: 601–33.

Lorch, R. P. 1995. “Ptolemy and Maslama on the Transformation of Circles into Circles in Stereographic Projection.” Archive for History of Exact Sciences 49, no. 3: 271–84.

Major, R. H. 1859. Early Voyages to Terra Australis, Now Called Australia: A Collection of Documents, and Extracts from Early Manuscript Maps, Illustrative of the History of Discovery on the Coasts of that Vast Island, from the Beginning of the Sixteenth Century to the Time of Captain Cook. Works issued by The Hakluyt Society, 1st ser., 25. London: Hakluyt Society.

Sidoli, Nathan, and J. L. Berggren. 2007. “The Arabic version of Ptolemy’s Planisphere or Flattening the Surface of the Sphere: Text, Translation, Commentary.” SCIAMVS 8: 37–139.

Van Duzer, Chet. 2020. “Urbano Monte’s World Maps: Sources and Development.” Imago temporis: medium Aevum 14: 415–35.

Walckenaer, Charles-Athanase. 1835. “Cartes géographiques (notice historiques).” In Encyclopédie des gens du monde, répertoire universel des sciences, des lettres et des arts: avec des notices sur les principales familles historiques et sur les personnages célèbres, morts et vivans, par une société de savans, de littérateurs et d’artistes, français et étrangers, 5.1: 11–18. 22 vols. Paris: Treuttel et Würtz.

Warner, Deborah Jean. 1979. The Sky Expolored: Celestial Cartography, 1500–1800. New York: Alan R. Liss for Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, Amsterdam.

Winsor, Justin. 1883. “A Bibliography of Ptolemy’s Geography [pt. 3].” Harvard University Bulletin 3(3): 164–70.

Zurla, Placido. 1806. Il mappemondo di fra Mauro camaldolese descritto ed illustrato. Venice.