Cognitive Maps in Bemazed Rats, and Humans

/How the Cartographic Ideal shaped Tolman’s (1948) interpretations of the nature of human spatial cognition

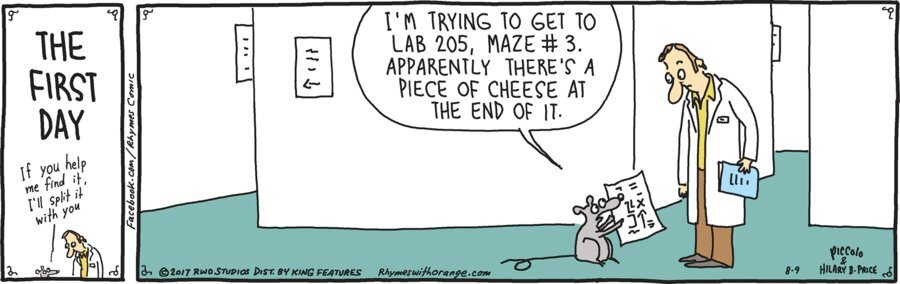

In quickly looking at some of the origins of the post-1945 study of cognitive maps—commonly but misleadingly called “mental maps”—I was led to a classic paper in behavioralist psychology: Edward C. Tolman’s “Cognitive Maps in Rats and Men” (1948). [All page references here are to this essay.] Tolman (1886–1959; PhD Harvard 1915) was a pioneer of behavioral psychology, working at UC–Berkeley (where he began in 1918), and was especially known for his studies of rats in mazes that greatly complicated the nature of the rewards system (Ritchie 1964).

The photographs that one can find online depict Tolman very much in the formal genre of the serious-humorless-conservative academic, but he was by modern standards a liberal—who staunchly defended academic freedom at Berkeley against McCarthyites in 1949–50—and he possess a marked sense of humor that he let shine in his scholarly writing. His sense of humor and social justice are evident in the opening paragraph of his 1948 essay:

Most of the rat investigations, which I shall report, were carried out in the Berkeley laboratory. But I shall also include, occasionally, accounts of the behavior of non-Berkeley rats who obviously have misspent their lives in out-of-State laboratories. Furthermore, in reporting our Berkeley experiments I shall have to omit a very great many. The ones I shall talk about were carried out by graduate students (or underpaid research assistants) who, supposedly, got some of their ideas from me. And a few, though a very few, were even carried out by me myself. [189]

The empirical study of maps in mazes led to certain conclusions about spatial cognition in rats. But as much as Tolman claimed to be following empirical procedures in applying those conclusions to human spatial cognition, his extrapolations were very much shaped by the ideal of cartography.

Tolman and his students used rats in mazes to study a wide variety of behavioralist topics, all ultimately concerned with understanding the relationship of stimulus to response. Tolman argued against overly simple constructions of that relationship. After several decades, he was able to synthesize a great deal of work that had implications for rats’ spatial cognition. The basic experimental model was to measure rats’ learning under different conditions (fed/hungry, expecting/not expecting a reward), but with judicious design a number of issues might be elucidated. In general terms, basic tests revealed:

the central office [brain] itself is far more like a map control room than it is like an old-fashioned telephone exchange. The stimuli, which are allowed in, are not connected by just simple one-to-one switches to the outgoing responses. Rather, the incoming impulses are usually worked over and elaborated in the central control room into a tentative, cognitive-like map of the environment. And it is this tentative map, indicating routes and paths and environmental relationships, which finally determines what responses, if any, the animal will finally release. [192]

That is, rats learn the maze not by direct stimulus-response but by building up a flexible cognitive map, one that might accommodate new information.

The further question for Tolman was whether rats develop a cognitive map from “relatively narrow” strips or “relatively broad and comprehensive” structures. Both kinds of cognitive map allow for learning and efficient action, but a comprehensive cognitive map offers greater flexibility and adaptability:

The differences between such strip maps and such comprehensive maps will appear only when the rat is later presented with some change within the given environment. Then, the narrower and more strip-like the original map, the less will it carry over successfully to the new problem; whereas, the wider and the more comprehensive it was, the more adequately it will serve in the new set-up. In a strip-map the given position of the animal is connected by only a relatively simple and single path to the position of the goal. In a comprehensive-map a wider arc of the environment is represented, so that, if the starting position of the animal be changed or variations in the specific routes be introduced, this wider map will allow the animal still to behave relatively correctly and to choose the appropriate new route. [193]

Ultimately, after describing many more experiments designed to elucidate this question, Tolman concluded that it was possible for rats to expand their strip cognitive maps into more comprehensive cognitive maps, but not fully so:

The spatial maps of these rats, when the animals were started from the opposite side of the room, were thus not completely adequate to the precise goal positions but were adequate as to the correct sides of the room. The maps of these animals were, in short, not altogether strip-like and narrow. [205]

That is, the strip cognitive map represented a lower or primary level of cognitive development, the comprehensive map a more fully developed level of cognition. Add to this conclusion an unspecified quantity of other research, and Tolman felt competent to make some comments about

the humanly significant and exciting problem: namely, what are the conditions which favor narrow strip-maps and what are those which tend to favor broad comprehensive maps not only in rats but also in men?

There is considerable evidence scattered throughout the literature bearing on this question both for rats and for men. Some of this evidence was obtained in Berkeley and some of it elsewhere. I have not time to present it in any detail. I can merely summarize it by saying that narrow strip maps rather than broad comprehensive maps seem to be induced: (1) by a damaged brain, (2) by an inadequate array of environmentally presented cues, (3) by an overdose of repetitions on the original trained-on path and (4) by the presence of too strongly motivational or of too strongly frustrating conditions. [205, 207]

That is, a cognitive map oriented by strips is prima facie indicative of poor or inadequate cognitive development. Anything less than a fully developed cognitive map must therefore indicate either childishness (not really defined, just dropped into the discussion) or psychological malfunction:

My argument will be brief, cavalier, and dogmatic. For I am not myself a clinician or a social psychologist. What I am going to say must be considered, therefore, simply as in the nature of a rat psychologist’s ratiocinations offered free.

By way of illustration, let me suggest that at least the three dynamisms called, respectively, “regression,” “fixation,” and “displacement of aggression onto outgroups” are expressions of cognitive maps which are too narrow and which get built up in us as a result of too violent motivation or of too intense frustration. [207]

If nothing else demonstrates the metaphorical nature of the “cognitive map” it is the manner in which reason and spatial understanding are ineluctably interconnected:

What in the name of Heaven and Psychology can we do about it? My only answer is to preach again the virtues of reason—of, that is, broad cognitive maps. And to suggest that the child-trainers and the world-planners of the future can only, if at all, bring about the presence of the required rationality (i.e., comprehensive maps) if they see to it that nobody's children are too over-motivated or too frustrated. Only then can these children learn to look before and after, learn to see that there are often round-about and safer paths to their quite proper goals… [208]

Ever the behavioralist, Tolman concluded,

We must, in short, subject our children and ourselves (as the kindly experimenter would his rats) to the optimal conditions of moderate motivation and of an absence of unnecessary frustrations, whenever we put them and ourselves before that great God-given maze which is our human world. [208]

There is so much here to unpack. Somehow the conflation of “cognitive map” with “world view” has led us from an instrumental practice of way finding and experiencing place as one moves through a landscape to the nature of one’s moral and global outlook. We have jumped scale, from place to space, from local intimacy (and what is more intimate than eating and rewards) to global empathy (or lack thereof). All collapsed within a metaphor that’s clearly actually more than a metaphor: it is the normative concept of “the map” rather than of specific spatial construct.

It might be logically acceptable that rats are not neurologically capable of possessing different kinds of cognitive map at the same time, but in presuming that humans are so cognitively limited, Tolman implied that the human cognitive map is grounded solely in experience and observation of spaces. This is the observational preconception of the ideal repackaged and wedded to the individualistic preconception. Indeed, Tolman seems to hold that cognition can only be a single process: all thought occurring in the same way, through the same set of cognitive wiring.

I also have to wonder about Tolman’s conclusions in light of the psychological study of cognitive development, à la Jean Piaget in the 1920s and 1930s. In laying out the stages of cognitive development as a series of spatial attainments, Piaget placed strip-cognition way finding as a marker of childish and non-Western cognition, a stage which Western children would outgrow as they developed a fuller and more flexible cognitive map. Tolman does not reproduce Piaget’s racist formulation, but the implications are there. Certainly, he reveals the same conflation of a flexible, comprehensive cognitive map with a flexible, adaptable world view. Rats can’t quite achieve that flexibility, but humans can, and should.

The lesson: don’t let the metaphor of the cognitive map cease to be figurative and become literal.

References

Ritchie, Benbow F. 1964. “Edward Chace Tolman, April 14, 1886–November 19, 1959.” Biographical Memoirs [of the National Academy of Sciences] 88: 291–324. ** largely a transcription of Tolman’s 1952 autobiography

Tolman, Edward C. 1948. “Cognitive Maps in Rats and Men.” Psychological Review 55, no. 4: 189–208.