Identifying Map Projections ...

/At a combined memorial event for Arthur Robinson and David Woodward, Joel Morrison recollected walking down State Street near the UW campus and listening to David’s running commentary about the often improper or inept use of different typefaces on the storefronts. This would have been in the later 1960s, when very few people other than graphic designers knew anything about typefaces and their qualities. But then Apple came out with the first Macintosh desktop computers in 1984 and introduced the world to graphic user interfaces and to the Joy of Fonts. (David was an early adopter and devoté of all things Mac.) Today, we all have opinions about different typefaces: the use of Times New Roman is a mark of an unimaginative mind, and lovers of Comic Sans are true font freaks!

In the same way, the proliferation of GIS applications has dramatically opened up the public appreciation of the many different kinds of map projections. When I first studied map projections, using Derek Maling’s Coordinate Systems and Map Projections (1973), it was an arcane topic limited to surveyors and map makers. John Snyder’s technical publications for the US Geological Survey were readily available as public documents, but not common on the ground. (I list them at the end; they are all downloadable.) The debates prompted by Arno Peters and his claims for his own map projection stimulated greater interest that has been fed by the ability of computers to spit out the world in almost any shape. Today we all have our favorite world map projections, and one’s choice says much about us as individuals!

I was just reminded of a really useful resource to help identify maps projections that one might encounter in the wild, at least projections designed before 1945. A student wrote a brief commentary on a large world map from 1907, with lots of information about the USA and its place in the world. The map’s title was “The World, upon a Globular Projection…”:

The term “globular” was used in eighteenth-century Britain to refer to any world projection that used curved meridians and parallels in an effort to capture the sense of the earth as a globe. Aaron Arrowsmith (1794) then used the term for a compromise projection that he introduced for a new double-hemisphere wall map; distorting less than the stereographic projection commonly used for double-hemisphere maps, other geographers rapidly adopted Arrowsmith’s projection.

But this 1907 map “upon a globular projection” is plainly not a double-hemisphere world map. The bumf under the title made claims about the quality of the projection, implicitly criticizing Mercator’s. But which projection is it?

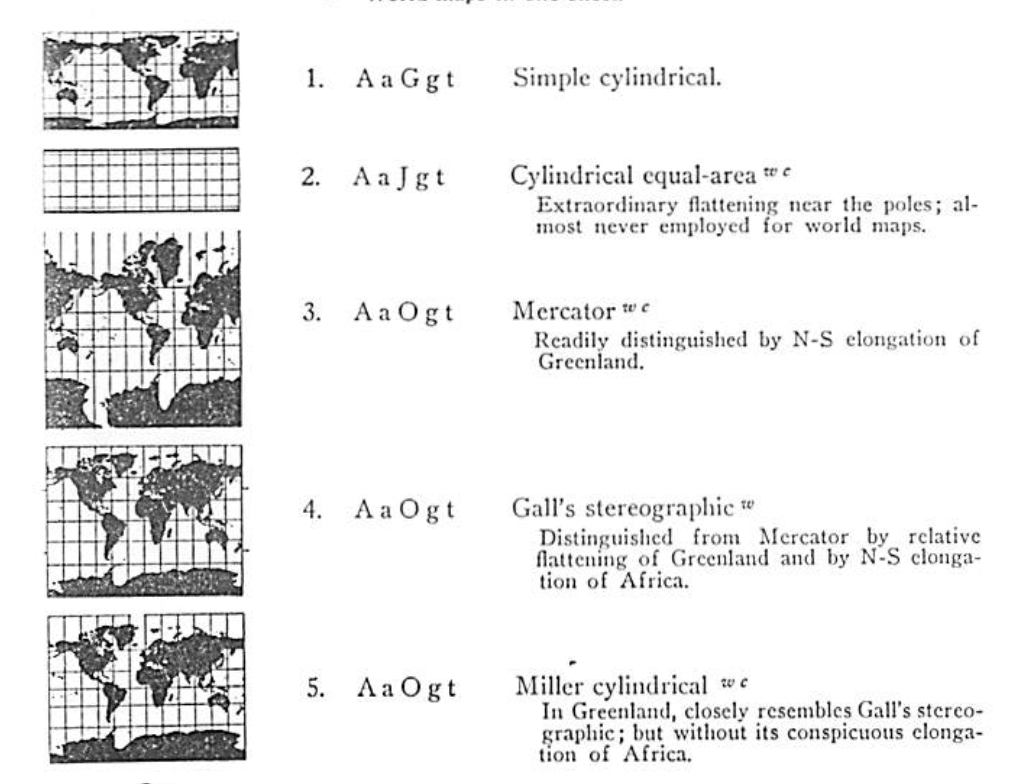

So I turned to the manual of map cataloging by Samuel W. Boggs and Dorothy Cornwall Lewis (1945). (One can borrow the book from archive.org - so check it out, just not all at once!) §2 of this book (pp. 81–95) deals with map projections from the point of view of the cataloger rather than the map maker. Boggs and Lewis therefore ignored the usual division of map projections by form of developable surface (planar/azimuthal, conical, cylindrical, and the pseudo-conical and pseudo-cylindrical) and by property (conformality, equal-area, etc.). Instead, they defined projections by how they look.

One first examines the forms and spacing of the meridians and parallels; different patterns generate certain codes. One then looks up the code in sequence to find the projection. Further superscript codes by each projection indicate the common usage of the projection. For example:

In the 1907 map I was interested in, the parallels are straight (A) and the meridians are curves but not arcs of circles (c); the parallels are all parallel and their separation decreases away from the equator (J); the meridians are equally spaced along each parallel (h); and the meridians and parallels intersect at oblique angles away from the central meridian and the equator (u). The map projection thus has the code: AcJhu. There are actually several projections that meet these criteria:

Given the comment in the map’s bumf that this projection allowed the easy comparison of the areas of different regions and the greater curvature of the meridians, I concluded that the map is not one of the eumorphic projections but is the Mollweide. This makes sense as the Mollweide was touted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as a replacement for Mercator’s projection. Bernard Cahill (1913, 159–61) complained about the distortions inherent to both the Mercator and the Mollweide, suggesting a degree of commonality in the latter.

The last question is why should the makers of the 1907 “globular” map have not used the more common name? My guess is that the makers sought to emphasize the map’s difference from Mercator in terms understandable to the layman, to give a sense of the nature of the projection without turning off the potential buyer with too many technical terms. It was, after all, produced by the “Home Educator Company,” presumably for use in classrooms and at home.

A Challenge

How might one expand and update Boggs and Lewis’s identification process to account for the new maps created and used since 1945?

Arrowsmith, Aaron. 1794. A Companion to a Map of the World. London: George Bigg for the Author.

Boggs, Samuel W., and Dorothy Cornwall Lewis. 1945. The Classification and Cataloging of Maps and Atlases. New York: Special Libraries Association.

Cahill, Bernard J. S. 1913. “A Land Map of the World on a New Projection.” Journal of the Association of Engineering Societies 51, no. 4: 153–207. Reprinted as An Account of a Land Map of the World on a New and Original Projection Invented by B. J. S. Cahill, A.I.A., F.R.G.S. (Delivered before the Technical Society of the Pacific Coast) (San Francsisco: The Author, nd).

Snyder, John P. 1983. Map Projections Used by the U.S. Geological Survey. US Geological Survey, Bulletin 1532. 2d ed. Washington, DC: GPO. Available online

Snyder, John P. 1987. Map Projections: A Working Manual. US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 1395. Washington, DC: GPO. Available online

Snyder, John P., and Harry Steward. 1988. Bibliography of Map Projections. US Geologial Survey, Bulletin 1856. Washington, DC: GPO. Available online

Snyder, John P., and Philip M. Voxland. 1989. An Album of Map Projections. US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 1453. Washington, DC: GPO. Available online