New England Prospect: An Innovative Map Exhibition from 1980

/update 6 February 2025: I have added a lot of material cut out of the intro to Maps as no longer using this exhibition as the starting vignette.

I’ve been looking at the catalog to another remarkable and innovative map exhibition that I would have loved to have been able to see in person. The folklorist Peter Benes installed New England Prospect at the Currier Gallery of Art in Manchester, New Hampshire, between 21 June and 2 September 1980 (just before I began my undergraduate career at University College London and two years before I ever realized that the field of map history even existed). The show featured no less than 132 [n1] seventeenth- and eighteenth-century maps, plans, and views from or about New England, plus some instruments too. Fortunately, a detailed catalog was published in the following year, which remains an essential resource for anyone interested in the early mapping of the region (Benes 1981).

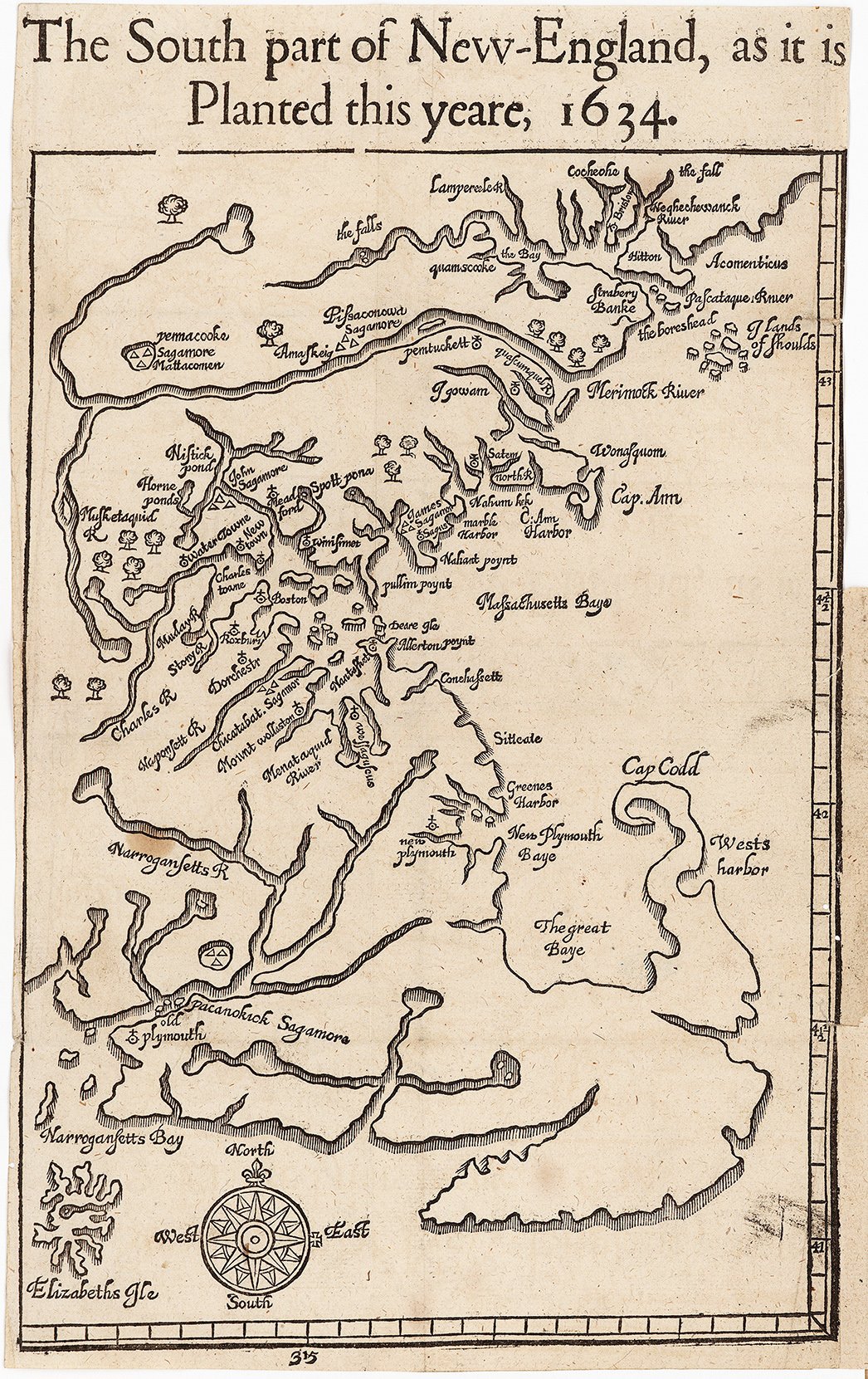

Benes took the exhibition’s title from that of William Wood’s account of early English colonization in and around Massachusetts Bay: New Englands Prospect: A True, Lively, and Experimentall Description of that Part of America, Commonly Called New England. By “experimental” was meant “empirical,” “by experience,” or “based on evidence”: this was an account of what had been achieved by Plymouth Colony since 1620 and by the Puritans in and around Massachusetts Bay since their first settlement (or “plantation”) at Salem in 1628 (Wood 1634). It was not a report written for the English Crown but an account by a colonist to entice potential colonists. [n2] (Not that the author has been precisely identified: see Vaughan’s introduction in Wood 1977.) Wood’s book included, opposite the first page of text, the first printed map of the earliest English settlements (Benes 1981, no. 5). The map’s crudely executed features are strongly suggestive of unpolished folk practices:

The South part of New-England, as it is Planted this yeare, 1634, in William Wood, New Englands Prospect: A True, Lively, and Experimentall Description of that Part of America, Commonly Called New England (1634, opp. 1). Note: “planted” meant colonized or settled. Click on image to view online at the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University (D634 W881n [R]).

Benes’ exhibition fascinates me for four historiographical reasons:

(1) it captures a point of intellectual inflection as both map and folklore studies changed, so that it seems at once contemporary and outmoded;

(2) it discloses a particular thread of settler-colonial map history that is relatively well-known within its region yet obscure and unappreciated elsewhere;

(3) it exemplifies how different flavors of map history merged to create the image of “the history of cartography” as a field of study; and

(4) it demonstrates the paradox that drives my current book project, specifically that the conviction that “the map” is a single category of phenomena is thoroughly undermined by the wide range of forms and functions of the works on offer.

Occasion: The Dublin Seminars for New England Folklife

Peter Benes was a graduate student in the program in American & New England Studies at Boston University when, in 1976, he convened a symposium on the topic of early New England gravestones, held at the Dublin School in Dublin, New Hampshire. It was such a success that he immediately planned a symposium for 1977 on New England archaeology, and thus the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife was born. Selected papers from each annual seminar have been published by Boston University Press.

For the fifth seminar, held 27–29 June 1980, Benes invited eighteen speakers on the theme New England Prospect: Maps, Place Names, and the Historical Landscape, organized in four sets: respectively, on naming, mapping, using, and perceiving the land. Each set featured an expert commentator. A total of ninety-eight people participated over three days (Benes and Benes 1982, 5–7). The appendix to this post lists the full list of papers and resultant map historical publications.

And, Benes organized the exhibition New England Prospect as the focus for the seminar. Indeed, the second day of the seminar featured a series of gallery talks as well as formal presentations held in the Currier Gallery of Art. It would certainly have served as an introduction to the universe of colonial English mapping for the diverse array of scholars who attended the seminar, most of whom knew little about the subject.

Motivation: The Parallel Disciplinary Anxieties of Folklorists and Historians of Cartography

The 1970s and 1980s were a period of disciplinary anxiety for both folklorists and historians of cartography. A brief search of the folklore literature suggests that the two fields were similarly positioned in an era of rapid growth in academia and of great intellectual excitement. Both fields were then experiencing a marked surge in activity. Dan Ben-Amos’s complaint that “the present tasks of folklore research are rapidly mounting and there are never enough of us to shoulder them” parallels Brian Harley’s frequently voiced complaint that “the vineyard is large, but the workers are few” (Woodward 1992, 120). Both fields suffered from an obsession with collecting, whether the folklorist’s acquisition of “tales, songs, proverbs, and log cabins” or the map historian’s emphasis on antiquarian maps. Moreover, both fields were struggling to break away from parent disciplines, respectively anthropology and geography, in order to establish themselves as autonomous disciplines (Ben-Amos 1973, esp. 114; Blakemore and Harley 1980). By the later 1980s, both fields were pushing more “critical” approaches to their subject matters (see, e.g., Stahl 1988). I would go one step further and suggest that some participants in both fields used historiographical exercises to invent long intellectual traditions for their putative disciplines; at least, I can say that for certainty for the creation of “the history of cartography” (no one referred to a single field of study by that title until after 1945) and I get the impression—from my admittedly very brief foray into their literature—that I could say the same for the folklorists.

Benes convened the seminar and organized the exhibition at the intersection of these disciplinary anxieties. Folklorists knew little about early maps, and map historians were little concerned with folklore.

So, who was available to speak at the seminar? Who occupied the unusual intellectual ground between folklife and maps? Effectively, Benes asked two main kinds of scholar to reach out into the new middle ground: the contributors to the section on “naming the land” were folklorists and archaeological or anthropological allies, and those to “perceiving the land” were cultural historians of art and landscape who did not really engage with maps per se. The contributors to “mapping the land” and “using the land” were a medley of cultural historians and librarians interested in historical geography and local history. Three of the commentators were prominent historical geographers, and the fourth a geographically minded historian (Allen). That is, many of the contributors were interested in “reconstructive map history,” which is to say the study of early high-resolution maps grounded in original surveys for the purpose of studying past landscapes (Edney 2012a, 2012b are preliminary statements).

Of the several presentations, the “most appropriate to the Seminar’s folkloristic emphasis” was Richard Candee’s on the surveys and plans in Kittery and southern Maine by William and John Godsoe. Candee had initially been interested in architecture in seventeenth-century Maine, an interest which led him to the Godsoe’s drawings of buildings on their plans (Candee 1982):

Other presenters each had a similarly empirical encounter with early maps (Benes and Benes 1982, 6–7).

In addition, Benes acknowledged the work of settler-colonial map historians interested in tracing the formation of polities that would become modern independent states and the transfer to them of European culture. Their work, which Benes called “a long-standing tradition of cartographic antiquarianism” gave Benes something of a “methodological framework” for locating, identifying, and selecting early maps for the exhibition. Benes was especially appreciative of the work of members of the Massachusetts Historical Society in the later nineteenth century who had trawled European archives for works of interest that they then presented to their colleagues in Boston, notably Justin Winsor whose four-volume Memorial History of Boston (1880–1881) and eight-volume Narrative and Critical History of America (1884–1888) are replete with his map commentaries and facsimiles (Benes 1981, xvi–xvii).

Benes brought all these threads of scholarship together in a single “New England Map Bibliography,” ignoring the significant differences in research agendas and approaches to maps and instead grouping a wide variety of works in a single expression of the history of cartography (Benes and Benes 1982, 117–25).

Innovative Intentions: An Exhibition of Vernacular and Folk Maps?

At the time, folklorists tended to understand cultural expression as occurring in two registers: high and low. High culture was the work of trained, skilled, and literate professionals, commissioned by the aristocracy, and was the subject of academic studies of art, literature, architecture, and cartography. Low culture was the work of the folk—of “everyday people who lived below the level of historical scrutiny”—who knew little, if anything, of the conventions and practices of high culture but who followed “vernacular” and “illiterate” practices (Benes 1981, xv). High culture was Mozart and Rembrandt, low culture was Morris dancing and gravestone art. High culture might plunder low culture for inspiration, but there was no counter flow. (This was by definition: once exposed to high culture, one pursued high culture.) The task of the folklorist was to discern and preserve manifestations of folk life without their preemption and distortion by contemporary aristocrats and present-day academic disciplines.

Folklorists had therefore shown no interest in early maps, and with good reason. Rooted as they appeared to be in the mathematics of measurement and calculation, maps were plainly part and parcel of elite practices of learning, government, and land ownership. Maps had nothing to do with folklife. Benes began, however, to reflect on maps and map making because of J. B. Jackson’s vigorous advocacy for the study of “vernacular” and “ordinary” landscapes (esp., Jackson 1970). How, Benes wondered, might everyday people have represented the landscapes in which they lived and worked? More particularly, how had English colonists in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century New England mapped the landscapes that they experienced and shaped? Wouldn’t their maps be fundamentally different from the professional maps made for British and French elites? Benes dedicated the seminar to the principle that

the New England landscape, like an artifact, was defined by prevailing cultural attitudes and assumptions. The region’s early topography was seen as reflecting the cummulative [sic] activities of people engaged in clearing fields, fencing off pasturelands, erecting stone walls, laying out roads, and building millponds and meetinghouses.

Like artifacts, landscapes are thus amenable to study by folklorists. In this respect, Benes treated early maps as sources of evidence to be interrogated to reveal past folkways and their impact on the environment:

The exhibition attempted to recover and re-create these activities and to document the larger region “folk” process of landscape making and landscape naming as it evolved in the region from 1500 to 1850 when European immigrants absorbed and replaced the Algonquian culture existing around them with English toponymic and agricultural traditions.

Benes echoed the arguments by Harley and other reconstructivist map historians of the need to contextualize the detailed, high-resolution maps of landscapes in order to assess their validity as evidentiary sources (esp. Harley 1968). It was necessary, Benes wrote, to establish the “intellectual and cultural matrix” within which the landscape and mapping processes took place:

What was the extent of map literacy in the region before 1850? Were there aesthetic components to this literacy? What were the relationships between colonial American and European mapmaking and naming traditions, both aristocratic and vernacular, as well as between colonial American and Algonquian mapmaking and naming traditions?

Benes therefore undertook a wide-ranging search of libraries and archives “beyond the usual repertory of printed maps associated with well-known events” for works that were “peripherally known vernacular or ‘folk’ documents.” He sought any folk or vernacular maps made by the English colonists that might reveal folk practices of “landscape making and landscape naming” (Benes 1981, xv).

Yet, after eighteenth months, he had found none. Benes soon had to accept that the entrenched aristocratic/vernacular duality was not actually manifested in the archival record of mapping by the English in New England. Rather, Benes and his collaborators came to recognize that map making was

an abstract, conceptual activity far removed from the experience of everyday people [that] in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was a military and measuring activity dependent on a relatively high level of technical knowledge and aesthetically grounded in long-standing European aristocratic tastes.

In this context,

because a trained or professional tradition in mapmaking and cartography did not evolve in America before 1790, vernacular maps—perhaps more accurately termed “working maps”—were the only kind that did exist in New England for the first two hundred years of the region’s history. (Benes 1981, xvi)

The regional map of New England in William Wood’s New Englands Prospect (above) appears as a crude attempt at trained map making. William Godsoe’s 1701 plan of property made for a legal case over probate (above) exemplified the markedly vernacular aesthetic of the “working maps,” especially his depictions of houses and in his characteristic compass roses, yet they were nonetheless grounded in technologies of measurement and property regulation that tied them inexorably with high, aristocratic culture. Benes used New England Prospect to show off some of these “working maps” and to demonstrate how they differed from the professional and elite maps of New England made on the far side of the Atlantic.

Benes had to look to the early-nineteenth century response to industrialization to find maps that eschewed formal geometries and professional standards and that can therefore be called “folk art.” He isolated a place map published to mark the settlement of the 1839 “Aroostook War” in the 1842 Treaty of Washington (a.k.a. Webster-Ashburton Treaty), which locates the British and US units in and around the disputed timber lands with a rather naively impressionistic delineation of geographical features (Benes 1981, no. 109). The map’s anamorphism might however have been a cynical attempt by the Boston publishers to give the map the aura of vernacular authenticity:

Execution: New England Prospect

Benes assembled his 132 exhibits in fifteen sections, generally arranging the items in chronological order:

I. New England Region: thirteen geographical maps from Cornelis Wytfliet’s 1597 map Norvmbega et Virginia (no. 1) to the 1777 French version of John Green’s (Bradock Mead) Map of the Most inhabited Part of New England (first published in 1775; no. 13).

II. Colonies, Counties, and Coastlines: nine mostly chorographical maps, from the so-called Winthrop map of Massachusetts Bay, ca. 1633 (no. 14), to a pair of school-girl maps of Essex County and Connecticut, from the 1830s (nos. 21–22).

III. Boundary Surveys and Disputes: ten maps and plans, of various kinds, all pertaining to boundary delimitation and disputes, from a regional map depicting Woodward & Saffary’s determination of points on the Massachusetts Bay/Connecticut border in 1642 (no. 23) to Caleb Butler’s 1825 boundary survey of the Massachusetts/New Hampshire border (no. 32).

IV. Town Surveys: eleven plans of towns, which is to say areas of relatively organized but dispersed settlement, from perhaps the first such map, of Chelmsford in 1656 (no. 33) to the division of Albany, Vermont, into lots in 1818 (no. 42), including several generated at the order of the governments of Massachusetts (1794) and New Hampshite (1803):

Aaron Everett, “A plan of the Town of Foxborough” (1795), at one inch to 200 rods (1:39,600). Each plan is unique, but most follow basic conventions in mapping boundaries, rivers, roads, and buildings. Aspects of Everett’s work—notably the heavy band of color on the outside of the town boundary, the oddly structured north arrow/compass rose, and the multiple orientations of the lettering—were naively unconventional. Benes (1981) included other town plans from the series. Click image to view online at the Massachusetts State Archives (Massachusetts Archives, Town Plans—1794, 1794-1795 [SC1/47X], 10: 4, no. 1215)

V. Phineas Merrill: six plans, both manuscript and printed, by Merrill of the town of Stratham, NH, and of the nucleated settlements of Exeter and Portsmouth (nos. 44–49), alas without shedding light on why Merrill had the maps printed.

VI. Boston: eight maps and plans of Boston and its environs, from the 1688 plan of the harbor by Philip Wells (no. 50) to a similar plan embroidered on silk in 1799 (no. 57).

VII. Parish Separation and Meetinghouse Locations: seven plans of towns from petitions to colonial authorities for the division of existing towns or the relocation of meeting houses, from 1667 through 1772 (nos. 58–64).

VIII. Memory Maps & Architectural Inventories: ten plans of rural towns and nucleated settlements showing buildings in profile, being generally historical works of the character of communities in the past, from 1748 (in an 1806 facsimile) to 1852 (nos. 65–74).

IX. Farms, Lots, Estates, and Rights of Way: a medley of fourteen plans, from 1649 to 1786, ranging from colonial grants of farms to individuals, land lots subject to legal dispute, and planned roads (nos. 75–88), including the clerk’s copy of the plan by the Massachusett John Sassamon of land at Sepecan ceded by Metacom/King Philip (no. 78; see Pearce 1998, 169–74).

X. William & John Godsoe: seven plans (nos. 89–95) by this grandfather/grandson pair of surveyors who worked in southern Maine, including the 1701 plan of Humphrey Chadburn’s farm (no. 91; above), as discussed in the Seminar by Richard Candee.

XI. Forts, Mines, Wharves, Mills, and Rivers: a medley of seven plans of various engineering and environmental projects between 1745 and 1830 (nos. 96–102).

XII. Battles and Fires: a variety of seven maps and places associated with wars, from the 1638 plan of a Pequot defensive settlement published in London (no. 103) to the lithographed anamorphic plan of the Aroostook War (1843; no. 109; above).

XIII. Horns and Whale Teeth: five examples of maps engraved on bovine powder horns, mostly produced at the time of the Revolution (nos. 110–14), and one example of a scrimshawed whale’s tooth from 1820 (no. 115).

XIV. Surveying Tools: a surveyor’s chain from 1800 (no. 116), two surveyor’s compasses from the 1740s and 1750s (nos. 117–18), a surveyor’s notebook from the same era (no. 119), and a copy of the 1760 edition of John Love’s Geodæsia (no. 120).

XV. Perspective & Bird’s Eye Views: twelve views of urban places, notably Boston, from 1723 (in a 1795 facsimile) to 1807 (nos. 121–28), a series of landscape views from 1826 through 1833 (nos. 129–31), and finally an 1845 bird’s-eye map of the Shaker village at Alfred, Maine (no. 132).

The result was a substantial array of images, from detailed plans of individual property lots, to general maps of each colony or state, to maps of the whole of northeastern North America.

A Remarkable Variety

Benes’s display of both elite and working maps gave rise to the second remarkable aspect of his exhibition, specifically the sheer variety of maps that he brought together. The variety fascinated one seminar participant (Nicolaisen 1984), it fascinated me in 1984 when I bought and first studied the published catalog, and it still fascinates me today. To begin with, the maps variously embodied distinct spatial conceptions:

• geographical (15/132 or 11%) maps, some intended for atlases or books (15, 11%) (as fig. 1), and some for hanging on walls (3, 2%);

• marine maps of coastlines and inshore waters (2, 1%);

• maps and views of urban places and harbors (17, 13%), especially of Boston;

• plans made from surveys of the boundaries (2, 1%) and contents of, variously, provinces (15, 11%), grants and towns, especially for their division and relocation of meeting houses (55, 42%), and individual properties (26, 20%) (as fig. 2);

• plans of battles and fortresses; and

• landscape drawings and paintings.

Benes’s exhibits further varied in physical form and in how they had been consumed and preserved. In terms of their form, a number had been printed from carved wooden blocks (3, 2%) (as fig. 1), engraved copper plates (30, 23%), or lithographic stone (1); these had been created with varying degrees of skill in Boston and in the printing centers of Europe. There were also some artifacts—engraved gunpowder horns and scrimshawed whale’s teeth—that had been inscribed with maps (7, 5%). Most of the exhibits were manuscript works (87, 66%). While most of the exhibits had been drawn by English colonists (106, 80%), some had been drawn by native interlocutors, and a number were products of skilled and experienced map makers in London, Paris, and Amsterdam (23, 17%).

The variety of institutions from which Benes sourced the exhibits suggests significant differences in how the maps had originally circulated. The printed maps had originally been sold in the public marketplace, they had been preserved on the shelves and in the cabinets of gentleman’s libraries, and they had been acquired by the special collections departments of university and public libraries, whether by gift from genteel owners or by purchase from antiquarian dealers (30, 23%) (as fig. 1). Official and legal documents (48, 36%), generally in manuscript, had been preserved in national, state, county, and town archives (28, 21%) (as fig. 2). Finally, the manuscripts from the private collections and archives of old New England families were sourced from the state and local historical societies in which they had been deposited (69, 52%).

All told, Benes’s exhibits entailed different spatial conceptions, at either fine or coarse resolution, in different media, and in different aesthetic styles. They fulfilled different functions for different groups of consumers. Their variety increases still further when we consider the maps that Benes excluded from consideration because they did not pertain directly to New England’s colonial landscape, such as marine charts and verbal maps. Such variegation in map form and function becomes almost dizzying when we look beyond the restricted spatiotemporal and cultural limits of early New England to consider maps from other periods, places, and cultures.

Innovative and Outmoded at the Same Time

This variety stemmed from the manner in which Benes blended established knowledge and new concerns. The blend made New England Prospect at once innovative and old fashioned.

It is perhaps difficult today to appreciate just how uncommon was its combination of materials. The idealization of maps as properly metrical images of the world might make it seem that fine-resolution and coarse-resolution works were always combined in map exhibitions and literature, yet scholarly practices tended to keep them isolated and distinct. Most map historians, including settler-colonial map historians, focused on coarse-resolution world and regional maps and charts. Academic cartographers extended that interest to moderate-resolution territorial maps. Reconstructive map historians, including the modern antiquaries interested in capturing the past in its relicts, studied maps made from original surveys, from moderate-resolution territorial maps to fine-resolution plans of towns and properties.

Previous map exhibitions, and for that matter written accounts of map history, had adhered to a pragmatic and institutional divide that had long been entrenched in modern culture. For example, of the forty-three exhibitions of early maps that Liz Baigent and Nick Millea (2020, 301) identified as having been mounted by the British Museum\Library in the century after 1880, all but one focused on either coarse-resolution mapping by geographers and mariners or on fine-resolution mappings by surveyors and engineers.

The several threads of map historical scholarship only began to intersect in the 1960s and 1970s, giving rise to the sense that there was a single field of “the history of cartography.” The slow process of unification is evident in map exhibitions that combined both fine- and coarse-resolution works. One of the first was a pop-up exhibition at the BM on British mapping, in conjunction with the 1964 International Geographical Congress (Skelton 1967; not in Baigent and Millea 2020). The exception in the list of BM/BL exhibitions was a wide-ranging exhibition commemorating the bicentennial of the US Revolution, which also featured both coarse- and fine-resolution maps (Tyacke, O’Donoghue, Cobbe, et al. 1975). Benes’s New England Prospect exhibition thus marks a fundamentally new turn in map historical studies.

Yet there was much about the exhibition that perpetuated older practices. The initial two sections replicated the established “frame fracturing” narratives of settler-colonial map historians: as new information was gathered (section II), geographical maps had to get larger until they could no longer hold all the information and the spatial frame of the narrative had to break and refocus on a smaller region. Section I told the story of growth of the map, to the four-sheet wall map of New England by John Green, after which the narrative splits into histories of the mapping of particular colonies and states (see McCorkle 2001, esp. appendix).

More generally, the sections were arranged not by the form or function of the maps but by the areas depicted. Section VI on Boston makes this clear, containing as it did marine charts of the harbor, topographical maps of the city’s environs produced by military engineers, and detailed plans of the urban place on the Shawmut peninsula. Several of the maps seem to present-day eyes to be misplaced. The two manuscript chorographical maps by schoolgirls have far more in common with the embroidered silk map of Boston harbor than with other maps of parts of New England. The final item, showing the buildings in a Shaker community, perhaps belonged more properly in Section VIII. And so on. Of course, so many items offered Benes any number of potential groupings, but overall he opted for the intellectually conservative and conventional.

An Innate Conservatism: Maps Are All the Same

Throughout, and this is key, Benes continued to think about maps as works that reproduce the world in some fashion, and as such should be arranged by what they show, not by how and why they were made. Benes sits on the cusp of the realization that form and function, and not content, are essential in understanding the nature of maps as historical artifacts. For all Benes’s push to expand the scope of map studies and to think about maps as artifacts, he was restrained by modernist expectations of the interconnection of map and territory. I do not mean to seem overly critical: modernist restraint continues to this day to infect and retard studies of maps as social instruments and cultural documents.

Even as Benes revealed the significant diversity of spatial texts produced in one relatively short period in or about one particular region, he nonetheless presumed from the start that they all manifested a single elitist, mathematical practice that varied only superficially, in its aesthetic. Even as Benes demonstrated the multiplicity of the purposes (why), practices (how), people (who), physical forms (what), periods (when), and places (where) of mapping, he nonetheless insisted that all map making was “an abstract, conceptual activity far removed from the experience of everyday people.” In the early modern era, he wrote, map making was always “a military and measuring activity dependent on a relatively high level of technical knowledge and aesthetically grounded in long-standing European aristocratic tastes” (Benes 1981, xvi). The working maps from colonial New England, where there were no trained or professional map makers, were thus low-culture, vernacular, and pragmatic expressions of an otherwise high-culture, refined, and abstracted activity. Throughout New England Prospect, Benes understood all maps to be, first and foremost, replications of the earth’s surface: despite their obvious and at times significant differences, all maps are essentially the same. Benes’s exhibits might have varied considerably in aesthetic form, between the vernacular and the professional, but all seemed to be grounded in an educated concern for the measured replication of the earth’s surface. The many dissimilarities between the exhibits could not detract from Benes’s conviction that they all possessed an essential nature as reductions of the world to human scale.

Benes was not alone in his a priori insistence that maps constitute a singular category of phenomena, regardless of plentiful evidence to the contrary. The reviewer of the exhibition similarly noted, in the face of all the diversity on offer, that the assembled works “provide an excellent guide to the growth of cartographic literacy and to the personalities most actively and directly responsible for that growth,” as if there is but one line of cartographic development driven forward by key individuals (Nicolaisen 1984, 178).

This commitment to the unity of map making also manifested in another exhibition of early New England maps installed in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts shortly after New England Prospect. A group of social historians had begun work in 1975 on a major exhibition of seventeenth-century English material culture—arms and armor, portraiture, iron and silver smithing, woodworking, and so on—to mark the 350th anniversary in 1979 of the foundation of Boston. However, building works delayed both exhibition, called New England Begins, and the associated conference until 1982 (Fairbanks and Trent 1982, 1:xii; Hall and Allen 1984, xi). Whereas folklorists like Benes generally considered the English colonists to be farmers and laborers lacking in formal education, the social historians argued that the colonists had mostly come from urban centers and were already one or two generations removed from the land (Allen 1981). Indeed, the colonists exhibited a high level of literacy, sufficient to read the Bible and to write legal documents. The literate and material cultures of colonial New England were therefore multifaceted and were not reducible to a simple dichotomy of suave, elite, metropolitan sophistication versus unrefined, folk, rural primitiveness (see Bushman 1984).

The first section of New England Begins addressed the “social and cultural landscape.” David Grayson Allen (1982) presented thirty-four seventeenth-century maps of places in both England and New England. Allen argued that these early maps were all expressions of, and evidence for, a mix of high-culture and vernacular economic and landscape practices on both sides of the Atlantic. Significantly, Allen further portrayed the maps’ evident dissimilarities as stemming either from scale differences (property plans versus regional maps) or from subtle cultural variations. As with Benes, presumptions of the unity and homogeneity of the surveying and mapping of New England led Allen to overlook abundant evidence to the contrary.

Significance and Influence

All this is to say that Benes was part of the movement to dissolve older intellectual frameworks, a movement that laid the foundations for more recent studies of folklore and map history. But the movement kept going and soon left Benes behind. The strict distinction of aristocratic and vernacular culture has dissolved into gradations of colonial and transatlantic society that recognize the persistence of native peoples (as Hornsby 2005). Environmental history has become a matter of shifting cultural ecologies and cross-cultural exchange (as Cronon 1983; Merchant 1989). Overall, historians have abandoned the kind of Turnerian hypothesis inherent to folklore studies that the frontier experience had determined new cultural forms (“American”) in distinction to old world culture (“aristocratic”). Again, Benes’s concerns read as outdated.

Yet the mix of different kinds of maps would soon be replicated in other exhibitions and conferences. David Grayson Allen (1982) explored the transfer of surveying and mapping practices from England to New England in the seventeenth century, in the process significantly complicating the idea of social and cultural transfer and transformation (see also Allen 1981). The range of different kinds of maps would be repeated in the exhibition and conference marking the creation of the Smith Center for Cartographic Education at the University of Southern Maine (exhibition: Danforth 1988; proceedings: Baker et al. 1994). I followed a very similar pattern to Benes in the first exhibition I curated for the newly recast Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education on the Cartographic Creation of New England (1996–97). Most recently, the argument that “modern cartography” began as part of the geometricization of renaissance Europe has generated an argument that all the mapping of colonial North America, from the surveying and mapping of lots of property to chorographical maps of the colonies themselves, is a single process of geometricizing space as territory (Greer 2018; Goettlich 2021).

Paradox

This leads me to my final point, and why I have been paying such close attention to Benes’s 1980 seminar and exhibition. For Benes, and for subsequent historians who had become alert to studying all kinds of mapping, maps might lie on a stylistic continuum ranging from professional through working to folk imagery, yet they nonetheless do not vary in their essential function of delineating spatial relationships.

It is perverse, in the face of Benes’s particular assemblage and of the still more diverse universe of spatial texts, to presume that there is only ever a single category of phenomena that are unambiguously “maps.” There is absolutely nothing special about Benes’s—or Allen’s—attitudes to maps and mapping. Their exhibitions stand only as examples of the culturally hegemonic expectation that cartography is a singular, universal, and literate endeavor whose inscribed products—maps—constitute a coherent, non-folk, and exceptional category of phenomena that reduce the world for human comprehension. There are occasional signs that some commentators do appreciate the sheer variety of maps. For example, one recent incomer to map studies concluded that “a bestiary of maps would be large and diverse,” given that “even traditional cartographic maps…do [not] fit into a single well-defined category” (Bruce 2021, 133–62, esp. 133). Even so, and indicating how normative expectations of cartographic universalism and exceptionalism remain deeply rooted in modern culture, this commentator immediately sabotaged his realization by asking, “what is a map?” A map, singular. Cartographic normativity and exceptionalism continue to shape both scholarly and popular map work:

There remains a prevailing view that maps are neutral and objective, once paper and now digital, accurate and functional, despite the now well-used line that maps are arguments made about the world. (Duggan 2024, 22)

Why should this be so? Why should all the manifest differences between maps be persistently set aside in favor of one apparently common attribute of “mapness” defined as a direct relationship between earth and image? Why should all the manifest variations in that relationship be simply ignored? These are the questions that drive the current book project. Stay tuned for more!

Appendix: Proceedings of the 1980 Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife

Taken from Benes and Benes (1982, 132), with small typos corrected. The four papers that were published are given in bold (full reference in the list of works cited). Related publications for other papers are also cited.

New England Prospect: Maps, Place Names, and the Historical Landscape

Naming the Land

Edwin A. Churchill, Maine State Museum: “Aboriginal Place Names in Maine” [see Churchill 1989]

Eugene Green, Boston University: “Naming and Mapping Massachusetts, 1620–1776” [Green 1982]

W. F. H. Nicolaisen, SUNY Binghamton: “Place Names in Early New England Literature”

Arthur J. Krim, Massachusetts Historical Commission: “Boston Basin Toponymy”

Wilbur Zelinsky, Pennsylvania State University: commentary

Mapping the Land

Sinclair H. Hitchings, Boston Public Library: “The Iconography of Boston Harbor”

Richard M. Candee, Kittery, Maine: “Godsoe Family Surveyors of Kittery, Maine”

Susan Danforth, John Carter Brown Library: “Osgood Carleton, Mapmaker” [Danforth 1983]

Robert P. Emlen, Rhode Island Historical Society: “Shaker Village Maps in New England” [Emlen 1987]

Mary T. Glaser, New England Document Conservation Center: “Map Preservation”

J. Kevin Graffagnino, Bailey Library, University of Vermont: “Maps as Historical Sources” [Graffagnino 1983]

Michael P. Conzen, University of Chicago: commentary

Using the Land

Christopher Collier, University of Bridgeport: “The Six by Six Townships”

James L. Garvin, New Hampshire Historical Society: “The Range Township in New Hampshire”

Stewart G. McHenry, Charlotte, Vermont: “The Cultural Landscape of Northern New England”

Thomas J. Schlereth, University of Notre Dame: “The New England Presence on the Midwestern Landscape” [Schlereth 1983]

David G. Allen, Massachusetts Historical Society: commentary

Perceiving the Land

John R. Stilgoe, Harvard University: “Shape-Shifting Land: New England Coastal Topography, 1600–1865”

John Opie, Duquesne University: “Puritan Theology and the American Wilderness”

Carol Zurawski, Boston University: “Folk Landscape Painting”

Robert L. McGrath, Dartmouth College: “Northern New England in the American Imagination”

Douglas R. McManis, Geographical Review: commentary

Notes

n1. The published catalog (Benes 1981) discussed 132 items. The introduction to the published lectures (Benes and Benes 1982, ••) states that the exhibition included 136 items, but I think that this is a typo.

n2. For completeness, I should note that J. K. Wright had similarly used the same title for his edited volume addressing the current state and future prospects of the region (Wright 1933).

Works Cited

Allen, David Grayson. 1981. In English Ways: The Movement of Societies and the Transferal of English Local Law and Custom to Massachusetts Bay in the Seventeenth Century. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Va.

———. 1982. “Vacuum Domicilium: The Social and Cultural Landscape of Seventeenth-Century New England.” In New England Begins: The Seventeenth Century, 3 vols., ed. Jonathan L. Fairbanks and Robert F. Trent, 1: 1–52. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

Baigent, Elizabeth, and Nick Millea. 2020. “‘Intelligent Strangers as well as Members’: Enlightening Maps and Social and Political Spaces for Cartographic Conversations.” Cartographic Journal 57, no. 4: 294–311.

Baker, Emerson W., Edwin A. Churchill, Richard D’Abate, Kristine L. Jones, Victor A. Konrad, and Harald E. L. Prins, eds. 1994. American Beginnings: Exploration, Culture, and Cartography in the Land of Norumbega. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Ben-Amos, Dan. 1973. “A History of Folklore Studies: Why Do We Need It?” Journal of the Folklore Institute 10, no. 1–2: 113–24.

Benes, Peter. 1981. New England Prospect: A Loan Exhibition of Maps at The Currier Gallery of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire. Boston: Boston University for the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife.

Benes, Peter, and Jane M. Benes, eds. 1982. New England Prospect: Maps, Place Names, and the Historical Landscape. The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife, Annual Proceedings, 1980. Boston: Boston University Press.

Blakemore, Michael J., and J. B. Harley. 1980. “Concepts in the History of Cartography: A Review and Perspective.” Cartographica 17, no. 4: Monograph 26.

Bruce, Bertram C. 2021. Thinking with Maps: Understanding the World through Spatialization. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bushman, Richard L. 1984. “American High-Style and Vernacular Cultures.” In Colonial British America: Essays in the New History of the Early Modern Era, ed. Jack P. Greene, and J. R. Pole, 345–83. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Candee, Richard M. 1982. “Land Surveys of William and John Godsoe of Kittery, Maine: 1689–1769.” In Benes and Benes (1982, 9–46).

Cronon, William. 1983. Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. New York: Hill & Wang.

Churchill, Edwin A. 1989. “Evolution of Maine Place Names.” Maine Historical Society Quarterly 29, no. 2: 66–90.

Danforth, Susan L. 1983. “The First Official Maps of Maine and Massachusetts.” Imago Mundi 35: 37–57.

———. 1988. The Land of Norumbega: Maine in the Age of Exploration and Settlement. Portland: Maine Humanities Council.

Duggan, Mike. 2024. All Mapped Out: How Maps Shape Us. London: Reaktion.

Edney, Matthew H. 1996–97. “The Cartographic Creation of New England: An Exhibition at the Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine, 6 November 1996 to 27 April 1997.” https://oshermaps.org/exhibitions/creation-of-new-england/.

———. 2005. “The Origins and Development of J. B. Harley’s Cartographic Theories.” Cartographica 40, nos. 1–2: Monograph 54.

———. 2012a. “Cartography’s ‘Scientific Reformation’ and the Study of Topographical Mapping in the Modern Era.” In History of Cartography: International Symposium of the ICA Commission, 2010, ed. Elri Liebenberg and Imre Josef Demhardt, 287–303. Heidelberg: Springer for the International Cartographic Association.

———. 2012b. “Field / Map: An Historiographic Review and Reconsideration.” In Scientists and Scholars in the Field: Studies in the History of Fieldwork and Expeditions, ed. Kristian H. Nielsen, Michael Harbsmeier, and Christopher J. Ries, 431–56. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

———. 2015. “Histories of Cartography.” In Cartography in the Twentieth Century, ed. Mark Monmonier, 607–14. Vol. 6 of The History of Cartography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Emlen, Robert P. 1987. Shaker Village Views: Illustrated Maps and Landscape Drawings by Shaker Artists of the Nineteenth Century. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Fairbanks, Jonathan L., and Robert F. Trent, eds. 1982. New England Begins: The Seventeenth Century. 3 vols. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

Garvin, James L. 1982. “The Range Township in Eighteenth-Century New Hampshire.” In Benes and Benes (1982, 47–68).

Goettlich, Kerry. 2021. “Surveying in British North America: A Homology of Property and Territory.” In Mapping, Connectivity, and the Making of European Empires, ed. Luis Lobo-Guerrero, Laura Lo Presti, and Filipe Dos Reis, 77–104. Lanham, CT: Rowman & Littlefield.

Graffagnino, J. Kevin. 1983. The Shaping of Vermont: From the Wilderness to the Centennial, 1749–1877. Bennington, VT: The Bennington Museum.

Green, Eugene. 1982. “Naming and Mapping the Environments of Early Massachusetts, 1620–1776.” Names 30, no. 2: 77–92.

Greer, Allan. 2018. Property and Dispossession: Natives, Empires and Land in Early North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hall, David D., and David Grayson Allen, eds. 1984. Seventeenth-Century New England: A Conference Held by The Colonial Society of Massachusetts, June 18 and 19, 1982. Boston: The Colonial Society of Massachusetts.

Harley, J. B. 1968. “The Evaluation of Early Maps: Towards a Methodology.” Imago Mundi 22: 62–74.

Hornsby, Stephen J. 2005. British Atlantic, American Frontier: Spaces of Power in Early Modern British America. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Jackson, J. B. 1970. Landscapes: Selected Writings of J. B. Jackson. Ed. Ervin H. Zube. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Krim, Arthur J. 1982. “Acculturation of the New England Landscape: Native and English Toponymy of Eastern Massachusetts.” In Benes and Benes (1982, 69–88).

McCorkle, Barbara B. 2001. New England in Early Printed Maps, 1513 to 1800: An Illustrated Carto-Bibliography. Providence, RI: John Carter Brown Library.

McGrath, Robert L. 1982. “Ideality and Actuality: The Landscape of Northern New England.” In Benes and Benes (1982, 106–16).

Merchant, Carolyn. 1989. Ecological Revolutions: Nature, Gender, and Science in New England. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Nicolaisen, W. F. H. 1984. “Peter Benes, New England Prospect: A Loan Exhibiiton of Maps at the Currier Gallery of Art (Boston: Boston University Press, 1981).” American Cartographer 11, no. 2: 177–78.

Pearce, Margaret Wickens. 1998. “Native Mapping in Southern New England Indian Deeds.” In Cartographic Encounters: Perspectives on Native American Mapmaking and Map Use, ed. G. Malcolm Lewis, 157–86. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schlereth, Thomas J. 1983. “The New England Presence on the Midwestern Landscape.” Old Northwest 9, no. 2: 125–42.

Skelton, R. A. 1967. “Exhibition of the Mapping of Britain, 13th–19th Centuries.” In Congress Proceedings: 20th International Geographical Congress, ed. J. Wreford Watson, 199. London: Nelson.

Stahl, Sandra Dolby. 1988. “Critical Studies in Folklore Historiography: Guest Editor’s Introduction.” Western Folklore 47, no. 4: 235–43.

Stilgoe, John R. 1982. “A New England Coastal Wilderness.” In Benes and Benes (1982, 89–105). Also published in Geographical Review 71, no. 1 (1981): 33–50.

Tyacke, Sarah, Yolande O’Donoghue, Hugh Cobbe, et al. 1975. The American War of Independence, 1775–83: A Commemorative Exhibition Organized by the Map Library and the Department of Manuscripts of the British Library Reference Division. London: The British Library.

Winsor, Justin, ed. 1880–1881. The Memorial History of Boston, Including Suffolk County, Massachusetts, 1660–1880. 4 vols. Boston: James R. Osgood.

———, ed. 1884–89. Narrative and Critical History of America. 8 vols. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Wood, William. 1634. New Englands Prospect. A true, lively, and experimentall description of that part of America, commonly called New England: discovering the state of that Countrie, both as it stands to our new-come English Planters; and to the old Native Inhabitants. Laying downe that which may both enrich the knowledge of the mind-travelling Reader, or benefit the future Voyager. London: by Thomas Cotes for John Bellamie.

———. 1977. New England’s Prospect. Ed. Alden T. Vaughan. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Woodward, David. 1992. “J. B. Harley (1932–1991).” Imago Mundi 44: 120–25.

Wright, J. K., ed. 1933. New England’s Prospect: 1933. New York: American Geographical Society.